When the state evicts community agencies

Despite a crisis in homelessness and a desperate need for expanded mental health services, the state evict a community agency

The men and women who gathered at the front steps of RIDE headquarters called for an independent investigation be conducted into what had occurred regarding the metrics around alleged graduation inflation in the Providence Public Schools.

They asked that the next session of the General Assembly move to put an end to the state takeover of the Providence schools – and to remove the powers of the current state education commissioner. They asked that a special Senate Oversight Committee hearing be convened.

Together, they also made it perfectly clear that they were talking about the future of the black and brown students to thrive in the Providence public schools, that they were speaking up on behalf of the teachers, students and parents. To succeed, they said they were calling out the persistent racism of the system.

Not surprisingly, the story did not get much play in the media. Much like the community activists who were shut out of the decision-making regarding the Providence City Council Finance Committee’s attempts to push through a new lease for ProvPort the night before the news conference, they gave voice to their anger. The question is: who is listening?

PROVIDENCE – A professor of American musical blues and heart ache, Tom Waits, once penned a lyric that captured the inherent nature of American capitalism, in his song, “Step Right Up.”

Step right up. Everyone's winner. Bargains galore.The closing lines, after a humorous if not tragic journey through the jargon of advertising slogans and come-ons, captured the bathos of consumerism: “The large print giveth, and the small print taketh away.”

That was the lyric ConvergenceRI found himself singing out loud after a source sent him the news that Community Care Alliance of Rhode Island, the nonprofit community agency headquartered in Woonsocket, had been notified by the legal counsel for the R.I. Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities, and Hospitals that the agency was being evicted from the state-owned property located at 181 Cumberland Street in Woonsocket.

The eviction notice was the exclamation point on a sad, years-long saga, involving both the Raimondo administration and the McKee administration, reported on in great detail by ConvergenceRI.

Even during a time of growing need for facilities to address the burgeoning demand for community-based mental health and behavioral health services, the state apparently had no appetite to invest resources in rehabilitation of its own, state-owned building, where the state’s failure to conduct proper maintenance, repair and upkeep, following a leak from the roof, resulted in the demise of the building.

[See links below to ConvergenceRI stories, “Is the state guilty of neglect with its community assets in Woonsocket?” “Investing in human infrastructure,” “Less is just less,” and “No shelter from the storm.”]

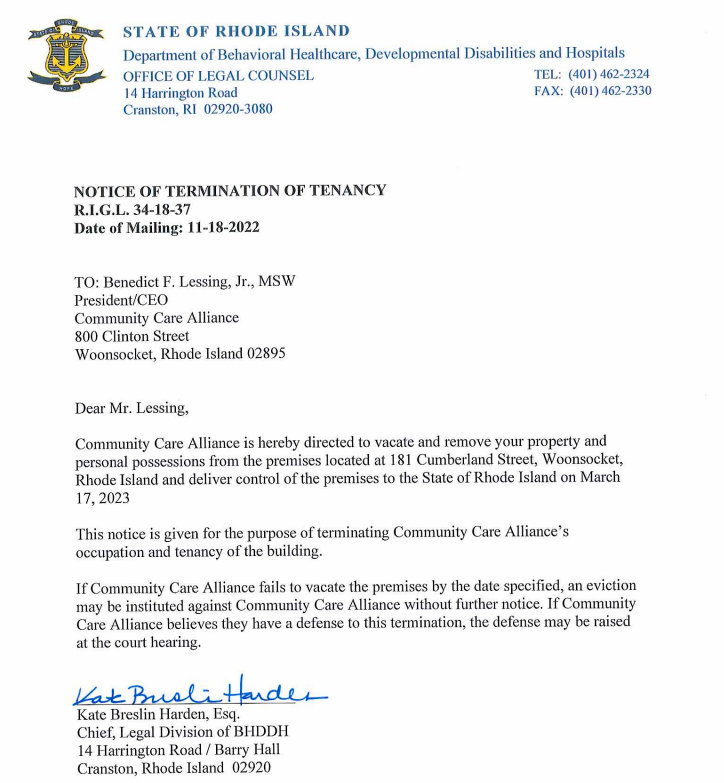

The eviction notice, mailed out on Nov. 18, 2022, by Kate Breslin Harden, Chief of the Legal Division at BHDDH, gave Community Care Alliance 90 days to remove its property and personal possessions from 181 Cumberland St.

The great irony, of course, is that less than a week later, the landlord, the state, after evicting the tenant, Community Care Alliance, from the state-owned building, the R.I. Department of Administration signed a purchase order for $1.44 million for the Community Care Alliance, in order to fund a temporary housing shelter to serve the “unhoused” population at the Sure Stay Hotel located on Route 116 in Smithfield. [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “A homeless shelter grows in Smithfield.”

Translated, as Tom Waits put it so aptly, “The large print giveth and the small print taketh away.”

The rest is commentary

One would be hard-pressed to invent the plot for a made-for-TV series that captured the apparent absurd contradictions in state policy.

“The state in their wisdom thinks that this is the right thing to do by evicting services out of their buildings who have paid rent for years,” said John J. Tassoni, Jr., the president and CEO of the Substance Use and Mental Health Leadership of Rhode Island. “The hospitals will be overwhelmed, and people will not get services,” Tassoni continued. “More deaths, more overdoses and mental health issues.

Further, Tassoni said, the problem did not appear to be a lack of state resources. “With a $660 million [budget] surplus, you would think that this would be money well spent to keep people out of the hospitals.” There are also “the billions from the federal government.”

“I just don’t understand,” Tassoni said. “Most of Rhode Island folks are one paycheck from sleeping in their cars or in the shelters. The system has collapsed.”

Instead of evicting Communiity Care Alliance from its 181 Cumberland St. facility, Tassoni suggested, “We need to get [everybody] into a room and solve this, ASAP. Lock the doors, and nobody leaves until we have a solution.”

A failure of policy, vision and leadership

Benedict Lessing, Jr., the long-time president and CEO of Community Care Alliance, was equally perplexed by the eviction.

“The state’s decision to sell the property operated as a community mental health center site at 181 Cumberland St. is a policy, vision and leadership failure, beginning with R.I. BHDDH and R.I. EOHHS,” Lessing wrote to ConvergenceRI.

“It is another indication of the disinvestment of the behavioral health system’s infrastructure that has been occurring in Rhode Island over the past 20 years, up to the present,” Lessing continued.

The lack of understanding by the R.I. Department of Administration and the R.I. Division of Capital Asset Management & Maintenance [DCAMM], Lessing said, about “the critical role these facilities have contributed to local communities and the system of care,and their disconnect with BHDDH, is disturbing.”

Lessing made the argument that sites such as 181 Cumberland St. “have saved the state millions of dollars over the past 40 years by providing services locally, thereby averting the need for expensive hospital-level care. Ironically, this decision occurs at a point in time when Rhode Island has an exploding “unhoused” population, many of whom suffer from serious mental illness and addiction.”

Lessing continued: “Hospitals across the state are struggling beyond their capacity, with Emergency Departments’ boarding adults and even children for days, weeks and, at times, months. There is a plethora of evidence regarding DCAMM’s failure to adequately maintain state-owned health and human service sites.”

Lessing then asked the pointed question about policy priorities out loud: “Yet, where has been the accountability across multiple administrations? Where is the oversight by the General Assembly?”

In the end, Lessing concluded it was the “disenfranchised populations, such as the ‘unhoused,’ and persons with mental illness and [substance use] concerns, [who] bear the consequences.”

Who is going to cover the story about the eviction?

Now that the 2022 election is over, reporting on policy decisions seems to have faded beyond the pay wall of many journalistic enterprises, in ConvergeneRI’s observation. The lights going dark at 181 Cumberland St. in Woonsocket is not as sexy a story as the lights being turned back on at the former Industrial Trust building in downtown Providence, or new restaurants being opened up to cater to the voracious appetites of Rhode Island’s foodies.

In New York City, Mayor Eric Adams has directed police and emergency medical workers to hospitalize people they deemed too mentally ill to are for themselves, even if they posed no threat to others, according to a report by The New York Times published on Tuesday, Nov. 29. One community advocate sent ConvergenceRI a copy of the story, saying: “This is what happens without sufficient community-based alternatives.”