The recovery community according to Jim Gillen [republished in his honor]

An in-depth interview about the future for the recovery community as it evolves in its role as a constituency of consequence [ConvergenceRI is republishing this interview in honor of Gillen, who died on July 18 after a long struggle with cancer]

As reported by Katie Davis on NBC 10 on April 27, at least 18 percent of people sent to Rhode Island’s ACI on any given day are arrested in connection with unpaid court costs, not because of a crime.

In other words, Rhode Island is running a debtors’ prison, at the direction of the judges, with much higher costs incurred by the state in keeping people in prison than the actual court fines. Perhaps the courts need a similar program to recovery coaches, in a system of legal advocates run by the Rhode Island Bar Association, to prevent this apparent miscarriage of justice. Perhaps members of the R.I. General Assembly may want to spend some time as court observers, to understand what is happening, and then take action to prevent it.

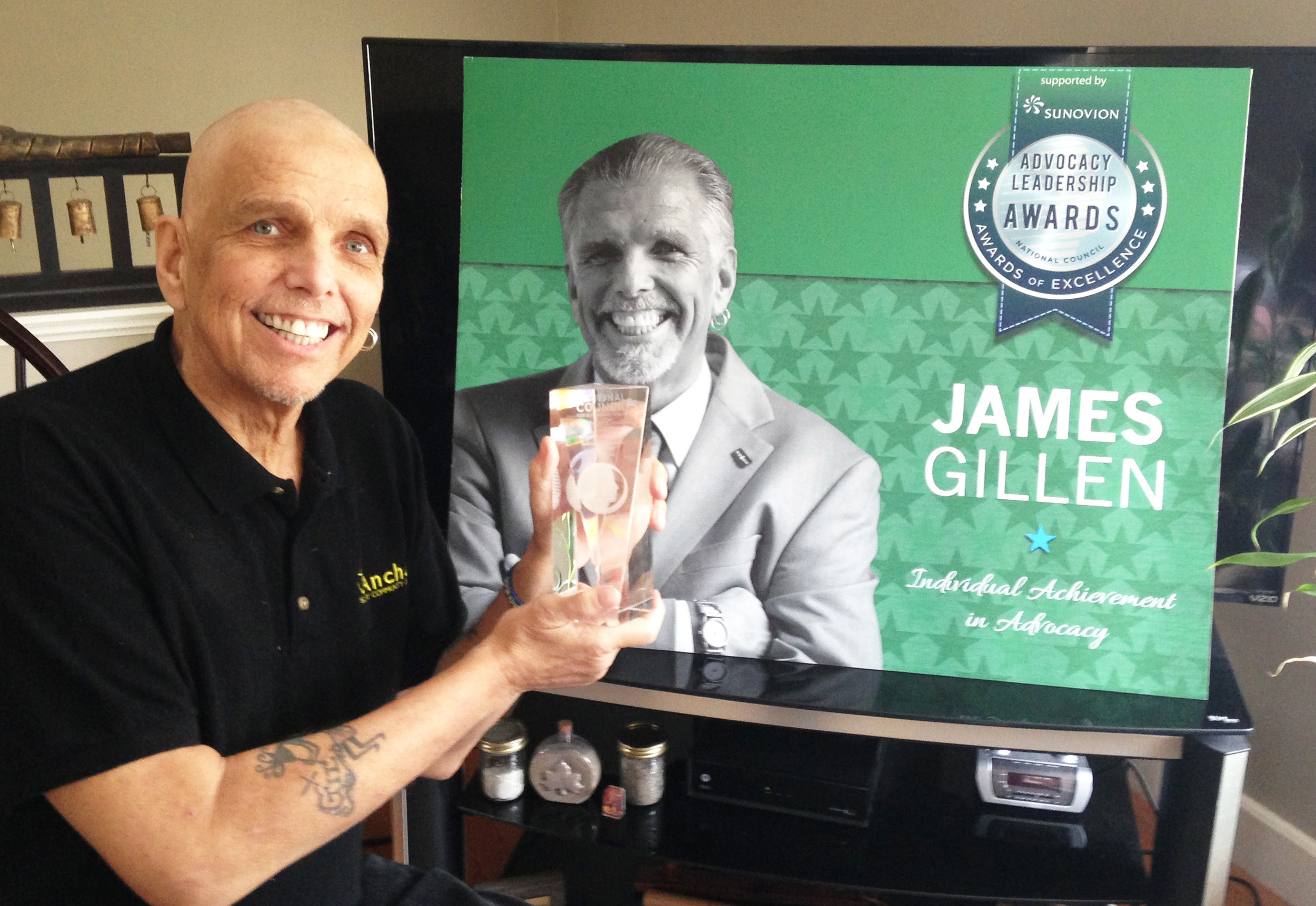

PAWTUCKET – When Jim Gillen smiles, it’s a big, infectious grin.

Gillen is the elder statesman of the recovery movement in Rhode Island, the manager of the Providence Center’s Anchor Recovery Community Center.

It’s been a season of recognition and awards for Gillen, who was honored in April for his advocacy by the National Council for Behavioral Health, receiving the 2015 Individual Achievement in Advocacy, at the organization’s national conference in Orlando, Fla.

In late February, Gillen was also received The John Kiffney Public Service Award, given by the Providence Newspaper Guild at this year’s Follies.

Gillen never misses a chance to drive home his point – often with a sense of humor.

“When I got that award from the Newspaper Guild,” he told ConvergenceRI in an interview on April 30, “I looked out and said: ‘If there’s anyone here from Electric Boat, where 20 percent of the people can’t pass the [drug] test, and now they’re looking outside of Rhode Island, come and see me. We can fill that 20 percent for you. We have the people who can pass the urine test, ready to work, and they have skills.”

The people [who are] in recovery now,” Gillen continued, “there’s a lot of talented people, some of the most creative dynamic people I know, and God knows, relentless.”

Both awards focused in part on Gillen’s role in developing an innovative, cutting-edge response to the epidemic of accidental overdose deaths in Rhode Island, known as Anchor ED. It placed certified peer recovery coaches, on call, every weekend from 8 p.m. Friday through 8 a.m. Monday, at emergency rooms at participating Rhode Island hospitals, to connect overdose patients with treatment and recovery options. [Weekends had been identified as a time when frequent overdoses occurred.]

The success of the program had been documented in a report, “AnchorED: A Care and Treatment Approach to Opioid Addictions, released on Feb. 9 [See link below to ConvergenceRI story.]

Gillen had introduced recovery coaching in Rhode Island in 2005; state certification was introduced in 2014. There are now some 85 certified recovery coaches in Rhode Island, having completed a 30-hour training program, performed 500 hours of supervised service in the recovery field, and passed an exam administered by the R.I. Board of Certification.

On the day that ConvergenceRI sat down to talk with Gillen at his home, the latest group of 14 new certified recovery coaches were recognized in the special State House ceremony organized by Rep. Patricia Serpa and Sen. Joshua Miller.

The latest class of new certified coaches was, in Gillen’s words, something that made him smile. The next generation of leaders in Rhode Island’s recovery community, he told ConvergenceRI, were special. “I watch them and they’re doing stuff that is amazing, and for me, that brings a big smile to my face.”

Here is the interview with Gillen, talking about the current landscape of the recovery movement in Rhode Island, where it’s been, and where it’s going.

ConvergenceRI: Can you frame the landscape of recovery, past, present and future? From the aspirations to become a constituency of consequence, how you got there, and now, here’s where we are, and here’s where we need to go.

GILLEN: Now, after many years, we’re recognized as a community that not only just registers to vote, but one that votes, and one that is very active in the legislative process.

That’s a big thing; in the past, they always kind of looked at us as – it’s a word I hate, but they looked at us as addicts – as people [that were] not going to vote anyway.

[All that has changed.] Yesterday was the national call in day for Sen. Whitehouse’s bill, [the bipartisan Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act]. We put the word out. People were on their cell phones all day, calling up and saying, “I’m one of your constituents. I urge you to support this bill.”

That really resonates with the lawmakers, because you’re a registered voter.

It has a lot to do with us becoming a constituency of consequence.

A couple of years, ago, there was a local state rep, it was when Patrick Kennedy decided not to run again.

So, I get a phone call from this guy, and he starts: “Jim, you know how much I support your issues…” He’s going on, and then, I realize, he’s working me, because he’s thinking about running for Kennedy’s seat, and that’s when the light bulb went off – d’oh, they’re finally getting it, that we matter.

We now have all these campaigns that “recovery matters.” That’s been a big thing. We’ve been invited to sit at the table; that’s a huge difference. People can see the value of peer support and the value of this community; we have valuable assets for the state and the nation.

ConvergenceRI: Where do we need to go from here? Is there still a disconnect around recovery? To move from being part of the conversation to being something that the state invests in?

GILLEN: It really needs to become part of the state budget, because it’s cost effective. It’s saving the state money; it’s really educating [folks] and showing how the costs of recovery coaching compare with the cost of being hospitalized.

It’s also the value of the peer approach. For years, as clinicians, we really had to stay away from that, because it was a different relationship. They would ask about that: are you in recovery? And, we would always be a little vague about it, from a clinical standpoint.

Now, all of sudden, they are embracing it; you can almost put in on your resume.

It’s putting people back to work. Everybody who works at The Anchor now, they all came in first, looking for help, or attending one of the meetings. And, then they volunteered, and then we ended up hiring them.

We’ve broken a lot of barriers with people on parole; how many job options do they really have?

This shows the value of peer support. It’s a national movement. I just think that here in Rhode Island, we’re a little ahead of the game nationally.

We’ve taken [peer recovery coaching] to this whole other level.

When we first started with recovery coaches in prison, it was unheard of.

Then, there was a recovery center at the prison, which was the next level.

So, now, where are we?

BHDDH [the R.I. Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals] was a huge part of our getting into hospitals, to really make it happen for us, a great collaboration.

Now, we’re in the hospital emergency rooms on weekends.

Talk is on the table to have us in those hospitals all the time, for [peer recovery coaches] to be involved, and not just in the emergency rooms.

Memorial Hospital is begging us to come in and help them with their patients.

Financially, and in manpower, we’re not able to do that yet. A proposal has been presented to the state; they want us in the hospitals 24/7.

ConvergenceRI: Is one of the next steps involved with housing for recovery? Something that creates an affordable bridge between a recovery program and re-entry into society?

GILLEN: When I first started at the Providence Center in 2008, the year before that, they had opened recovery apartments, called Wilson Street. It was innovative at the time, because it was like any affordable housing, it gave people a base to really start and build a foundation, without worrying about how am I going to pay the rent this week.

What we’d like to see is more of that. I would love to see [health insurers], at some point, deal with recovery housing.

ConvergenceRI: What is reimbursable now?

GILLEN: Recovery coaching is starting to be reimbursable now. The first in the country, through Optum Health [UnitedHealthcare], we have reimbursements for recovery coaching, because it’s cost-effective for them.

The other insurance companies are sure that we’re going to be knocking on the door. My goal is that, once all the insurance companies get on board with recovery coaching, then we start hitting them for recovery housing, but that could take some time.

It took us two years of romancing just to get where we are today.

ConvergenceRI: As part of the plans to reinvent Medicaid, one the plans mentioned is STOP, a way to provide police with an alternative from dropping the people they pick up for being inebriated at the emergency room. Is there a way to get the statistics for how many are being dropped off at emergency rooms?

GILLEN: I do know that sometimes, they’ll bring in the same person, five, six, 10 times a week, to the ER. It gets to the point, where the ERs are so overwhelmed with them, they just get sober enough, give them a turkey sandwich and send them on their way.

What happens is, they’re back out on the street, and now they go into full-blown withdrawal, if they don’t have the money to get a bottle.

ConvergenceRI: What’s the next level of conversation? What becomes the next tipping point?

GILLEN: I don’t know; I don’t have an answer.

ConvergenceRI: How will you know when we’ve gotten there? For instance, Tom Coderre in Washington, and his national agency director is someone in recovery. That’s brought about a whole different approach to the conversation.

GILLEN: I talk to Tom Coderre, maybe twice a week. [With a laugh and a smile.] I try to guilt him out, asking how he could just up and leave us. I often ask his opinion, or his advice.

One of the things that we’re hopeful about, if and when we do get access to emergency room diversion, and as we are able to more outreach on the street, is that we’ll be able to get a better handle on that data.

That’s a tough population to track, and as you well know, just trying to depend on the hospital or the police department for statistics, it’s not a priority. [In a different voice:] “Oh, Jimmy was here 10 times this week; what else do you want from me?” They would never say it like that.

People are starting to recognize that what we do is valuable. That to me, is also part of being that constituency of consequence.

ConvergenceRI: How do you measure the change in the conversation? Some of the language has changed, it’s a substance use disorder, it’s talking about recovery, it’s avoiding terms like clean and dirty. What’s the change in the conversation that will make you break out in one of your trademark big grins?

GILLEN: I guess I’m already grinning, because for me, what once was a dream is now a reachable goal.

You know, we have to be relentless. You know, I don’t think that I need anyone to say anything, but I need for them to show respect for what we’re doing.

We need to have the treatment providers embrace this recovery system of care. We really need treatment providers to take it to the next level.

With recovery, there’s got to be planning, particularly with the shorter stays now in treatment. You’ve got to get to planning, almost as soon as you stop shaking. What are you going to do when you get out?

People that come in [to recovery], either from drug or alcohol over use, they’re not really great planners; they’re used to planning one great misadventure to the next.

So, now we’re asking them: let’s plan out your immediate future, and how we’re going to do this in the most stress-free way.

They often say: I’ll figure it out.

I can’t tell you how many guys in prison that I would spend time with, when I asked them: so, you’re getting out next month, what’s the plan?

“Oh, I’m going to get a job. I’m going to get an apartment.”

Great, [I’d say]. How are you going to do that?

“I’ll figure it out.”

Then you’d see them in prison three months later, and ask: what happened?

It’s really about the planning.

Now, I’m going back to the hospitals to plan with them.

Memorial Hospital. I thought that they would never get it together, and now, they’re calling us all week long, even though, technically, we’re not open on weekdays.

I’m not going to say: Jeez, Richard, you overdosed, but can you come back on Friday?

We’re not going to do that; we’ve got to service them.

ConvergenceRI: What can the news media do better in covering the story?

GILLEN: It would be to focus on the many success stories, and on how many people are seizing the opportunity.

Today, the House and Senate are recognizing the next group of peer recovery coaches. These people are employable. We have people who are ready to work.

When I got that award from the Newspaper Guild, I looked out [at the audience] and said: If there’s anyone here from Electric Boat, [that said that] 20 percent of the people [who applied for jobs] can’t pass the drug test, so they’re looking outside of Rhode Island, I said, “Come and see me. We can fill that that 20 percent for you. We have people who can pass the urine test, who are ready to work, and they have skills.”

People in recovery now, there’s a lot of talented people, [some of] the most creative, dynamic, and God knows, relentless, that I’ve ever met.

If you’re a user [with a big grin], you’re constantly doing fundraising, constantly you’re doing problem solving, and you’ve been doing marketing now and then.

But, these people have skills; that’s what I’d like to focus on.

Abby is a young lady who works for us [as a peer recovery coach]; I stopped to see here yesterday. She said Sports Illustrated just contacted her, and they are interested in doing a story on young athletes who ran into problems with painkillers because of a sports injury.

This kid, she came to us [at Anchor] a couple of years ago, and Holly [Cekala] and I were sitting there, and she came in, drops her bag on the floor, she’s in tears, and she says: Jim, you have to help me, you have to help me.

We did our hustle, using the creative, dynamic approach, and got her into recovery housing. She’s now in school, she started as a volunteer, and now we’ve hired her.

ConvergenceRI: What haven’t I asked that I should have asked? What would you like to talk about? The last words are yours.

GILLEN: Two things. One, for me, is what I’m seeing that makes me smile.

In being sick, I’m in my second battle with lymphoma, my son just shaved off my hair, my hair was getting a little gray. It gives me the chance to wear a lot of cool hats, my old berets.

The stress involved in that, especially in a relapse, is sometimes unbelievable. I’m pretty stubborn, and I’m a fighter, which helps.

Sometimes, you don’t feel like fighting.

I’ve got my own control issues, you know.

I’m so used to doing everything, whether it’s sweeping the leaves out front, or it’s about the rally for recovery.

So, here I am, in an extremely limited capacity. Sometimes it’s frustrating, because I can’t do what I want.

But, it’s also been something of a joyous experience, because I’m watching everybody grow.

Holly Cekala has the potential to be a leader in the recovery [community] in Rhode Island for the next 20 years. She’s got the goods. We talk about [strategy] a lot; when to back off.

She’s got that rare combination of smarts, the drive, the passion, so watching her blossom at RICares [makes me smile.] She’s really taking it to the streets.

When I watch the Rally for Recovery, which is my baby, the people, they’re all rising up and they’re doing it.

It’s hard, because I always want to go and just fix everything. I watch them, and they’re doing stuff that is amazing, and for me, that brings a big smile to my face, because it’s allowing me to concentrate as much as possible on healing.

One of the things that Tom Coderre said to me, it was rally time, and I said: You know, Tom, it feels like I’m charging up the hill, with the bugle and I turn around, and there’s nobody there. I’m getting a little worn out by it.

So, he told me, he said: don’t you worry. I’m going to be running right along side of you. But, you’ve got to remember: we have to develop the next generation. And, by developing them, you have to let them make their own mistakes. Rather than saying, OK, I’m just going to do this.

You know, the support that I get, I don’t know how I would have dealt with this cancer if I wasn’t in recovery. I get an unbelievable amount of support, and it’s overwhelming sometimes.