In cold blood: poisoning our children

When man-made disasters are caused by budget austerity decisions made by state government managers, whom do you call to the rescue? The community

Editor's Note: This week, the film, "Dark Waters," based upon the story written by Nathaniel Rich in the Jan. 10, 2016, issue of The New York Times Magazine, began playing nationwide. The movie tells the story about how Dupont knowingly dumped tons of an unregulated toxic chemical known as perfluorooctanoic acid, or PFOA, used in the manufacture of Teflon.

Prompted by Rich's investigative reporting, I wrote about my early career as a journalist, and my pursuit of true crime stories, reporting on children and families that were being poisoned for profit. It seems appropriate to publish the story again, in the context of the film's release.

Some things have changed for the better since the story first ran. As a result of strong citizen opposition, the proposed Invenergy power station has been defeated. Young climate activists are continuing to press elected officials, including Gov. Gina Raimondo, to take a stand in favor of the Green New Deal.

Breast Cancer Action, an advocacy group, has mounted a campaign to "Say Never To Forever Chemicals," calling attention to the devastating health harms of PFAs, urging stronger federal regulation.

Some things have changed for the worse. Flint. Mich., continues to struggle with the effects of lead poisoning on children in the city. The Trump administration continues to pursue a poilcy of deregulation when it comes to environmental protection laws.

PROVIDENCE – In my early career as a journalist, I wrote a number of true crime stories, reporting on children and families that were being poisoned for profit.

It was a different genre than the work by Truman Capote or Raymond Chandler; the crimes did not take place on the mean streets of Los Angeles, or recount lurid details of four grisly murders in a Kansas farmhouse.

The dramas I covered occurred on the outskirts of the modern world or in the homes of suburban families, in a modern theater of the absurd, where the violence was not personal but impersonal and corporate, where the motives were not about lust or anger, greed or drunken rage, or a replay of Biblical conflicts between fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, but steely calculations made about achieving and protecting corporate profits.

The bottom line was that the victims were almost always “invisible” and deemed unimportant, their poisoning written off as the cost of doing business, in the name of progress.

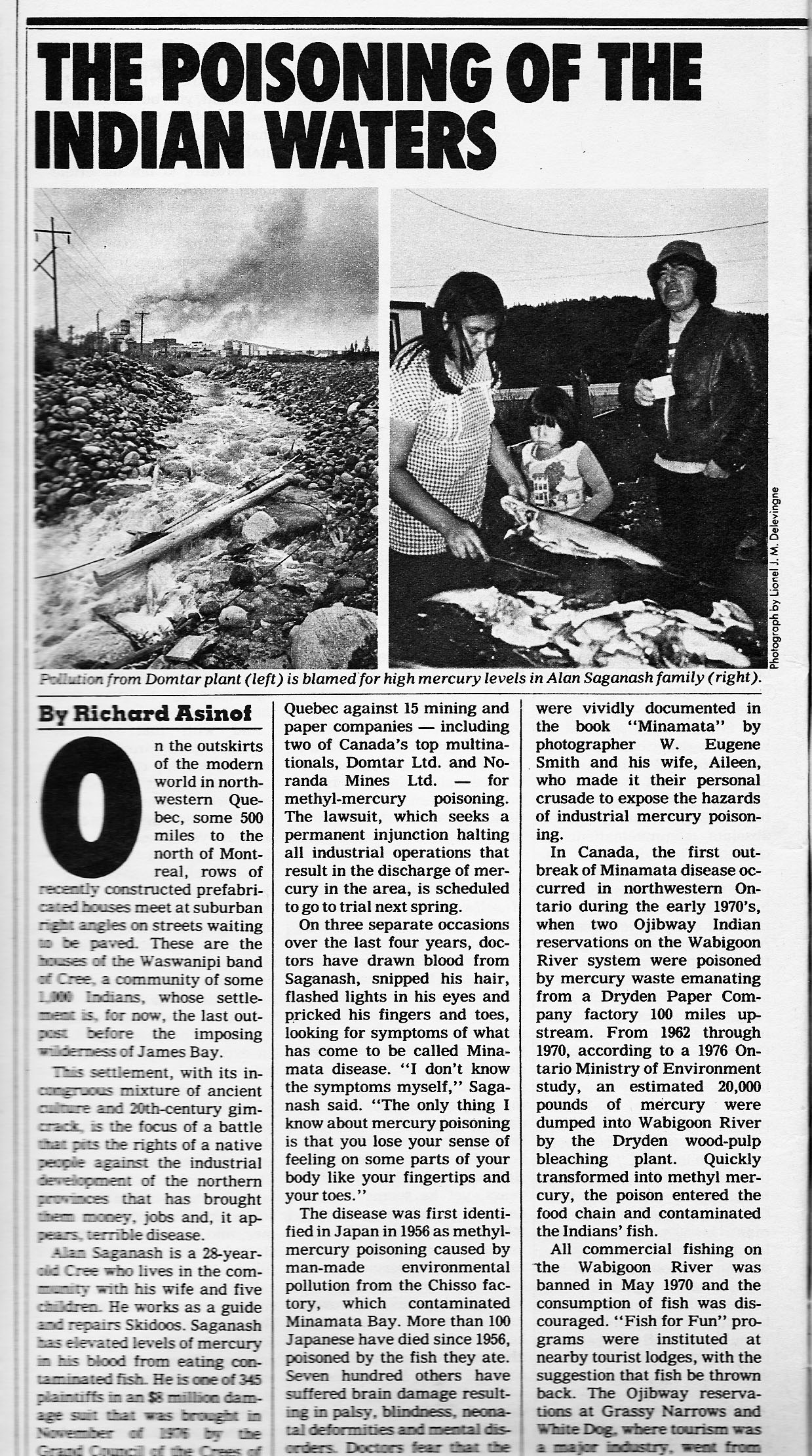

• In 1979, my story in The New York Times Magazine, “The Poisoning of the Indian Waters,” told how the Cree in northwestern Quebec had been poisoned by mercury.

One of the alleged culprits was a pulp-bleaching factory, which had used mercury as a constantly flowing electrode to produce the chlorine used to bleach the wood pulp, in an outdated technology. After about 20 years of delivering tons of mercury into the environment, and leaving a native culture in disarray, it closed down.

• In 1984, my op-ed in The Los Angeles Times, “We have toxic tragedies of our own,” was written in the aftermath of the travesty in Bhopal, India, where thousands were poisoned and died as a result of an explosion at a pesticide manufacturing plant, which had been producing a notoriously toxic pesticide, Temik.

In response to numerous reporters’ questions about whether “it” could happen here, I reported on the reality that it was indeed happening here, except that most people were unaware of it.

The piece urged that CEOs be held accountable for their actions, quoting a lawyer who led a task force on toxic crime in Los Angeles, saying that CEOs needed to hear the slam of the jail door behind them, because it would serve as an effective deterrent. That’s still very much true today.

• In 1987, my op-ed in The New York Times, “Is Vermont Third World?” questioned the economic wisdom of the plans to locate a landfill for toxic waste from a trash incinerator a stone’s throw away from the Battenkill River, one of America’s most revered trout streams, contrasting the economic advantages of a trash incinerator financed by a Japanese investors against the value of protecting Vermont’s natural resources.

Name the toxic threat – lead, mercury, PCBs, dioxin, incinerator ash, nuclear waste, pesticides, asbestos, and endocrine disruptors – and I had reported and edited stories about the toxic crimes that occurred, often covering places with infamous names on the toxic hit parade – Love Canal, Times Beach, Stringfellow, Woburn, Mass., Emelle, Ala., Barnwell, S.C., and most recently, Flint, Mich.

In reporting on these stories, I had interviewed numerous citizens, almost always women, who had courageously spoken up against the toxic threat: Lois Gibbs, Penny Newman in Los Angeles, Hazel Johnson in Chicago, Becky Hardee in South Carolina, Raye Fleming in San Luis Obispo, Anne Anderson in Woburn, and Carole Horowitz in Holyoke, Mass., among others.

On the other side of the divide, I had also interviewed numerous corporate spokesmen – champions of obfuscation, denial and sometimes, outright falsehoods. One spokesman from Pacific Gas & Electric told me, in earnest, that plutonium was safe enough to hold in your bare hands. Another spokesman from Domtar, the huge paper conglomerate, in response to my request for an interview, said he would get back to me shortly – but instead called my magazine editor and attempted to get my story killed. There was the senior vice-president from Waste Management, Inc., who, while driving me through Washington, D.C., kept looking, with pride, to see which dumpsters bore the company’s name.

And, there was also Jim Jenkins, U.S. Attorney General Edwin Meese’s spokesman, who, in response to my question in 1983, asking whether Meese, working with Rita Lavelle, had manipulated the settlements of hazardous waste site cleanups for political purposes, responded: “That’s the dumbest question I’ve ever heard. Are you asking whether Ed Meese committed a felony? The answer is no. No!” [It was a memorable denial, given Meese’s future legal problems about alleged felonies he was implicated in committing.]

Making money

Rereading these stories now, three and four decades later, I can recognize a common thread: the undercurrent of my anger about the insidious nature of the corporate philosophy that deemed the “externalities” of consequences from toxic pollution as something that was outside the traditional economic equation – a kind of recurring chronic dementia about the true costs of public health.

Let me repeat this: the victims were almost always “invisible” and their lives deemed unimportant, written off as the cost of doing business and progress. The damage being done was to the “other” – the folks seemingly on the outside – and not those perceived as “us.”

Connecting “them” to “us” often required a breach of etiquette in conversation – and in reporting.

Once, in my early 20s, when talking about my work reporting on the dangers of nuclear power at the family dinner table, an uncle asked me: why wasn’t I smarter, and consider switching sides, and make some money by investing in the utility industry, which was then booming.

He laughed, and everyone at the table joined in, making fun of my apparent folly.

I responded, in a calm voice: I didn’t think it was a good investment to give my money to companies whose profits were based on products that caused cancer in people. Did you?

The laughter stopped abruptly, followed by an awkward, uncomfortable silence. My uncle’s wife, sitting next to him at the table, was ill, struggling with the later stages of breast cancer, a well-known family secret that had never been discussed in public.

Vicarious vs. real

While we as a nation can never seem to get enough of the vicarious thrills of heart-stopping cinematic crime dramas filled with dead bodies, be they super heroes in an endless battle against villains, good cops vs. bad cops or spy vs. spy in the murky immoral world we inhabit, the genre of environmental reporting covering toxic crime has been out-of-style, passé for decades.

In the years since Ronald Reagan became President and the conservative political movement has been in ascendancy, environmentalists and regulators and the EPA have become the so-called enemy of the people.

It was, as Bruce Springsteen once sang [and David Bowie covered], hard to be a saint in the city, and it was even harder to be an environmental reporter telling tales of toxic crimes: the market for publishing such stories had dried up. Instead, there were new business journals in every city celebrating the art of the deal.

The pendulum may be swinging back. On Jan. 10, The New York Times Magazine published a compelling investigative story by Nathaniel Rich that detailed the way in which Dupont knowingly dumped tons of an unregulated toxic chemical known as perfluorooctanoic acid, or PFOA, used in the manufacture of Teflon. [See link to the story below.]

In Hoosick Falls, N.Y., state agencies are scrambling to deal with another apparent toxic poisoning from PFOA, warning citizens not to drink public water or use it for cooking because of the presence of the toxic chemical. The contamination has been allegedly linked to the Saint-Gobain Performance Plastics factory, located not far from the municipal wells that provide the small town with its drinking water. Once again, local citizens raised the alarm, forcing state officials into action.

The breach of etiquette by citizens in Flint, talking back, accusing state officials of negligence and worse, and demanding action in response to the travesty and tragedy that occurred as a result of the man-made poisoning of its city, may be catching. Watch out.

A generation of children poisoned

Much of the reporting and the legal questions about what happened in Flint are attempts to develop an accurate chronology of what happened – what did you know and when did you know it.

Here is the basic story line: the Republican governor of Michigan, Rick Snyder, with the twitter handle, @onetoughnerd, and a Republican-controlled legislature, following the roadmap laid out by ALEC, the conservative think tank funded by the Koch brothers, passed legislation allowing the state of Michigan to take over financially strapped cities and towns and manage them, outside the electoral process, in the name of budget austerity.

Even though the citizens of Michigan voted to repeal the law, the governor and the legislature struck back, tweaking the law, making it immune to future referendum, and re-enacted it.

A decision was then made under the new law by the state-appointed manager to save a few million dollars by connecting to the toxic Flint River instead of the current, more expensive connection to drinking water from Detroit, which came from Lake Huron. [The tourist slogan for Michigan to attract visitors, “Pure Michigan,” may have to be changed.]

The narrative gets a bit murky here. No anti-corrosive agents were ever added to the river water, despite its known toxicity. Apparently, no initial testing was done of the toxicity of the water. Later, when there were tests conducted, the results were allegedly manipulated to downplay the potential risks. Citizens’ complaints once the switch was made were ignored and downplayed by state officials; officials kept repeating the mantra that the water was safe to drink. [Where was Erin Brockovich, as portrayed in the movie by Julia Roberts, to offer the governor and state officials a glass of the dirty water to drink?]

An engineering professor from Virginia Tech University conducted tests and declared the water lead-contaminated. A local pediatrician did research on the lead levels in children, before and after the switch, and found that the number of children with elevated levels of lead had doubled. Still, state officials continued to challenge the findings until October of 2015. The federal EPA had numbers that documented the lead poisoning, but out of caution over its legal authority to do so, chose not to release the numbers.

Finally, the switch was made back to Detroit water, but the damage to the pipes had already been done, and the lead continued to flow in the water. Finally, in early January of this year, the governor declared a state of emergency and, most recently, directed the legislature pass some $28 million in emergency funds to help deal with the man-made crisis – to pay for filters, bottled water and the like.

The reality is that replacing the lead-leaching water pipes, damaged by the corrosive water of the Flint River, could cost as much as $1.5 billion – 55 times the amount of new emergency funds from the state.

And, the staggering reality of the true public health and education costs are only beginning to sink it.

In Flint, population of 100,000, with about 9,000 children under the age of six, an entire generation of children may have been poisoned by lead and sentenced to potential irreparable brain damage and a lifetime of health, education and economic disabilities, all under the guise of budget austerity.

Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, who directs the Pediatric Residency at Hurley Children’s Hospital in Flint, whose research helped to change the equation, sees the lead poisoning of Flint’s children and families as a long-term problem that needs a long-term follow-up – with a 20-year commitment. It is not about the creation of mass lead-testing clinics but the delivery of services that span numerous non-medical domains. [See the link below to her recommendations, which parallel recommendations made by Dr. Peter Simon in ConvergenceRI.]

Who’s going to rescue the families and children of Flint? While the Republican candidates for President were promising to eviscerate Obamacare, there was Republican Gov. Snyder of Michigan asking the feds to allow Medicaid eligibility be expanded to all children under 21 in Flint.

What is the proper role of government? The citizens of Flint – and not the state officials or the state managers – have an answer: they have realized that they need to be a partner in making decisions about their lives, and in doing so, reclaim their democratic rights.

Implications for Rhode Island

Underneath the surface, there are a number of events that could roil the traditional political equations being made by political and corporate leaders in Rhode Island by citizens asking to be a partner in making decisions about their lives.

• The mounting citizens’ opposition to the proposed natural gas power plant in Burrillville, to be built and owned by Invenergy, named the Clear River Energy Center, presents a growing challenge to Gov. Gina Raimondo’s stewardship. The planned power plant will run on fracked natural gas, but it will also be tooled to run on fuel oil. The need for the new power plant has been challenged – on both environmental and economic grounds. The state’s Energy Facilities Siting Board recently rejected numerous opponents’ claims that they had any standing to intervene, while pushing for an accelerated regulatory process. The first public hearing will be held on March 31, at the Burrillville High School cafeteria.

• A report by the Environmental Protection Agency said that more than 90 facilities in Rhode Island had released some 383,794 pounds of known toxic chemicals into the environment in 2014, an increase of some 81,310 pounds, or 20 percent. About 41 percent of the releases were emitted into the air. In comparison, the six New England states released some 16.5 million pounds of known toxic chemicals into the environment, a reduction of about 12 percent, or 2.2 million pounds. What’s the cost of these released toxic chemicals in terms of public health?

• Three separate citizens’ efforts to protect Narragansett Bay and the communities most at risk from the stew of toxic pollution could coalesce into a more powerful, engaged community. They include: continued opposition to the proposed new liquefied natural gas plant to be built by National Grid in the port of Providence, combined with questions raised by the Environmental Justice League of Rhode Island about environmental racism in Rhode Island, and growing concerns about the continued toxic pollution from scrap metal operations on Narragansett Bay and the apparent inability of state government or federal regulators to shut them down.

And, of course, there is the reality that there are still nearly 700 new children a year in Rhode Island that are being screened and diagnosed with elevated lead levels in their blood.