There is no planet B

The March for Science, here in Providence, across the nation and around the world, connects a new generation with environmental activism

Who would nominate to be recognized for a Rhode Island environmental hall of fame?

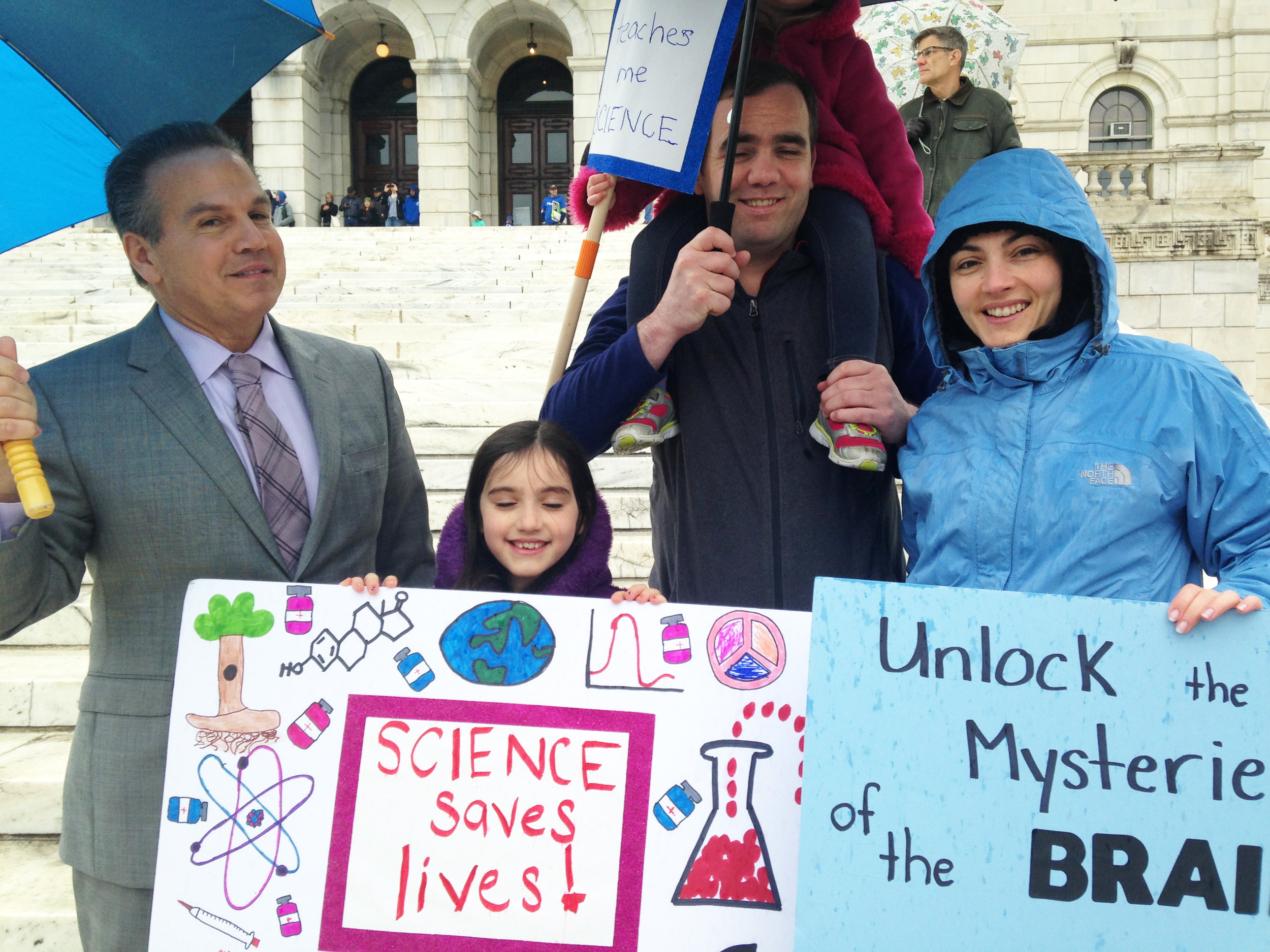

PROVIDENCE – It was a cold, rainy but glorious day for a March for Science in Providence on Earth Day, April 22.

More than a thousand demonstrators braved the weather to show their support for science, research, the environment and Mother Earth in a gathering on the south steps to the State House.

Like its sister marches around the nation and across the globe, there were an abundance of witty, homemade signs and earnest rhetoric from the stage – and a sense of camaraderie and resistance to the plans by the Trump administration to make dramatic cuts in scientific research and gut the work on climate change.

The closing song by the event performers, “Big Yellow Taxi,” by Joni Mitchell, with its iconic chorus, “Don’t it always seem to go/that you don’t know what you’ve got ‘til it's gone/They paved paradise/Put up a parking lot.”

Or, as one of the protesters' signs expressed eloquently: “There is no Planet B. To save our Earth, we must support science.”

Another family of protesters, a grandmother, a mother and two children, held signs that were emphatic in their beliefs about science: the grandmother, who said she was a truck driver, held up a sign that said, sternly: “The laws of physics must be obeyed. There will be consequences.”

But will the Trump administration listen? Will the Republican Congress listen?

A talk with a tribal elder

To gain some perspective, ConvergenceRI sought out Peter Harnik, one of the indefatigable organizers from the original efforts around Earth Day in 1970 and the development of the first national citizens’ environmental action group, Environmental Action.

Harnik had organized a group of former members of Environmental Action to walk together in the March for Science in Washington, D.C., including David Bryant, holding up an Acid Rain umbrella, once one of the fulfillment items that Environmental Action provided to members. For years, the group promoted its activities with the slogan, “Love Your Mother.’

At the March for Science, a number of fellow marchers came up to Bryant to ask: “What’s acid rain?” Call it both a sign of progress and perhaps, a generational divide around pressing environmental issues.

As Harnik aptly noted: “Most Americans living today weren’t born in 1970.”

And, for Harnik, the new wave of environmentalism feels like it is a circle coming around again.

“In 1970, when Richard Nixon was president, people back then were trying to make Americans conscious for the first time about the environmental threats to our air and water,” Harnik said. “And litter, what we do with the trash.”

The issues back than were around smog and more sophisticated issues like nuclear power and promoting renewal energy.

“Back in the 1970s, it was a steep learning curve, a steep hill to climb, to make Americans aware that there was even a problem,” Harnik said.

One of the “innovations” of Environmental Action was organizing political action by citizens, targeting Congressman who had been labeled “The Dirty Dozen,” tying them to their votes in favor of polluting industries. Much to the surprise of the political pundits, the campaign succeeded in unseating a number of Congressmen.

With the election of President Ronald Reagan in 1980, Harnik continued, much of a decade’s worth of progress on environmental issues was halted. “The Reagan counter-reformation occurred. Advances that had been made in the 1970s were attempted to be rolled back,” he said.

Much of everything that is happening today with the Trump administration, Harnik continued, happened in the 1980s, pointing to efforts to dismantle the EPA under Rita Lavelle and Anne Gorsuch Burford. [Yes, that’s the mother the newest Supreme Court Justice.]

“It was very similar, with a strong ideological opponents of the environment and [equally strong] proponents of corporate freedom and corporate power,” Harnik said.

Returned for regrooving

Another Earth Day organizer, Denis Hayes, talked about the deja vue all over again phenomenon, linking to what happened under Reagan to what could happen under Trump.

In an op-ed in The Los Angeles Times published on April 21, Hayes wrote:

“In its approach to scientific research, President Trump’s budget can be accurately described as a mugging. I’ve watched this happen before, up close and personal. It does not end well.

“In 1979, President Carter set an ambitious but achievable goal to get 20 percent of the nation’s energy from renewable sources by the year 2000. I then headed the federal Solar Energy Research Institute, which spearheaded the Manhattan Project to Harness the Sun. In the late 1970s, the United States had more Ph.D.s in the solar field, filed more solar patents and made more commercial solar modules than the rest of the nations in the world combined.

“In its first year, the Reagan administration slashed the solar institute’s staff by 40 percent, reduced its budget by 80 percent and abruptly terminated all of its 1,000-plus university research contracts [including shutting down work by two professors who later went on to win Nobel Prizes]. The firings were so wantonly brutal that many of the researchers were driven into other fields. The consequences have been huge.

“In 2016, solar energy was the United States’ largest source of new electricity-generating capacity, contributing roughly 40 percent of the total from all sources. The U.S. solar industry now employs 260,000 people, more than three times as many workers as the coal industry. Most of them install and maintain photovoltaic panels that convert free, nonpolluting sunlight into power.

“But nearly all the solar modules these workers install are being developed and manufactured abroad. The U.S. makes just 5 percent of the world’s solar panels.”

Connecting the dots in Rhode Island

The speakers at the March for Science rally at the State House did a good job of connecting the policy dots between science, alternative energy, public health and jobs – and the need to fund more research.

What was missing, perhaps, was the connection to corporate responsibility and the need to hold companies accountable for their actions.

In the aftermath of the natural gas pipeline rupture in Providence, RI Future’s Steven Ahlquist documented the fact that PCBs [polychlorinated biphenyls], a suspected human carcinogen, had been released during the mishap with the Spectra Energy gas pipeline that occurred on National Grid property at 30 Allens Ave. The R.I. Department of Environmental Management confirmed the fact that PCBs had been released during the leak, according to Ahlquist.

Although PCB production was banned in the U.S. since 1977, how best to clean up the mess left behind by the use of PCBs in products such as electrical transformers has dogged companies such as GE for years.

Even as GE plans to populate the location of its satellite office in Providence, and seeks to break ground on its new corporate headquarters in Boston, the PCB mess it left behind at its plant in Pittsfield, Mass., still remains unresolved.

As reported by Clarence Fanto on April 13 in The Berkshire Eagle:

“Five Berkshire County towns and an array of organizations have joined the government in the legal battle to prevent General Electric from dumping contaminated soil in a local landfill.

“The EPA has ordered the company to spend $613 million over 13 years to dredge, excavate and remove PCB-laden soil and sediment from hot spots, primarily in southeast Pittsfield, Lenox and Lee, and ship the toxins to a federally licensed, out-of-state facility.

“State regulations bar the disposal of PCBs into landfills since Massachusetts has no federally licensed disposal sites.

“The company argues that it would be safe and cost-effective to truck the contaminated material to a landfill near Woods Pond on the Lee-Lenox border, or to sites off Forest Street in Lee and near Rising Pond in the Great Barrington village of Housatonic. GE says it could save anywhere from $160 million to $245 million.

“The potential site at Lane Construction Co. off Woods Pond is 1,300 feet away from the village of Lenox Dale, the Berkshire Regional Planning Commission pointed out in the brief.

“In its filing to the Environmental Appeals Board, GE contends that the EPA cannot impose off-site disposal of toxic PCB waste as there is “no environmental benefit.” The company asserts that there are “no adverse environmental impacts associated with the out-of-state transport and disposal of sediment and soil. Safe, cost-effective local options exist.

“A three-judge panel at the Environmental Appeals Board in Washington, considered an independent arm of the EPA, is reviewing the case with a hearing set for June 8.”

In his story, Fanto quoted Lauren Gaherty, senior planner of the Regional Planning Commission, at length:

“The cost difference between the local and off-site disposal is only slightly more than the $119 million that GE paid its top five executives in 2015 alone,” Gaherty said in the story.

Gaherty also said that when the GE spent close to $2 billion to remove PCB contamination from the upper Hudson River, it also sought a local landfill instead of an out-of-state licensed site, as the EPA required., according to the story.

“GE fought the EPA every step of the way and the EPA prevailed,” Gaherty said, in the story.

The legacy of the PCB contamination in Pittsfield, according to the story, goes back eight decades. “[GE] released the probable cancer-causing toxins into the Housatonic [River] from its Pittsfield electric transformer plant from the 1930s until 1977, when the U.S. government banned the use of the chemicals,” according to the story.

“The company’s cost-savings argument rings hollow,” Gaherty contended, according to the story.

Truth, costs and consequences

For years, GE has battled with EPA to limit its responsibilities for the clean up of the PCB contamination in Pittsfield.

Pittsfield may seem far away from Boston, but they are both part of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Here in Rhode Island, as GE moves ahead with its new software division, and as environmentalists begin to ask questions about the economic and public health consequences of PCB contamination from the natural gas pipeline leak in Providence, the question is: what lessons can be learned from the tale of GE fighting to seek a cheaper alternative for its responsibility to clean up its own PCB mess?

In turn, how will those tasked with responsibilities for protecting the public health of citizens in Rhode Island educate themselves about the looming PCB problem as a result of the natural gas pipeline leak?

It is more than an academic exercise: as ConvergenceRI reported on, one of the translational collaborative research grants awarded went to researchers at URI to develop guidelines around when fish are contaminated with mercury and PCBs, are they safe to eat. [See link to ConvergenceRI story below.]

The larger question is, of course: who will be held liable for the costs of the clean up? National Grid? Spectra Energy? Algonquin? And, will state officials, including Gov. Gina Raimondo and Attorney General Peter Kilmartin, step up to demand a thorough clean up of the site?