The problem with rewriting news releases as news

Measuring the value of peer recovery coaching may demand the creation of new kinds of metrics

Covering the evolution of policy choices to address the continuing epidemic of overdose deaths and the diseases of despair, including suicide and alcohol as well as drugs, is often a slog through details. The stories do not fit easily into 500-word formats or 60-second blips in broadcast news.

Memories of what really happened keep getting distorted – both by lies from politicians and a peculiar kind of institutional amnesia when it comes to the news.

With the World Series about to begin on Tuesday, Oct. 23, as well as the drawing for the $1.6 billion jackpot in the Mega-Millions lottery, it is worth recalling that 99 years ago, the Chicago White Sox, in cahoots with gamblers, conspired to throw the 1919 World Series, a classic tale of American corruption. The definitive history of the scandal, Eight Men Out, was written by my uncle, Eliot Asinof.

In our current time of great corruption and great greed, it is tale worthy rereading – or, for those that don’t read, watching the John Sayles movie.

Editors Note: Peer recovery coaching in Rhode Island began four years ago in 2014 as an improvised solution developed by lay leaders of the recovery community, including the late Jim Gillen and Holly Cekala, to address the apparent clinical failures of the health care delivery system in addressing the needs of patients who survived drug ODs in hospital ERs.

Since then, peer recovery coaches have become an accepted best practice at emergency rooms across Rhode Island. The initial problems about how best to reimburse for such services that did not fit into the clinical framework appear to have been resolved, to some degree.

Now, a new, four-year clinical research study that seeks to determine the value of peer recovery coaches is being hailed by Brown University public relations in a news release as an example of how hospital ERs and academic researchers are fighting on the front lines against the opioid epidemic.

Is it a bit ironic that an innovative approach developed by the recovery community is now being championed as an example of hospital ERs and academic researchers being on the frontlines?

In the $800,000 study, the effectiveness of clinical social workers embedded at Rhode Island Hospital will be compared to that of peer recovery coaches in enrolling post-drug overdose patients in recovery programs and whether patients complete an 18-month recovery program. But, are those the right metrics to be measuring?

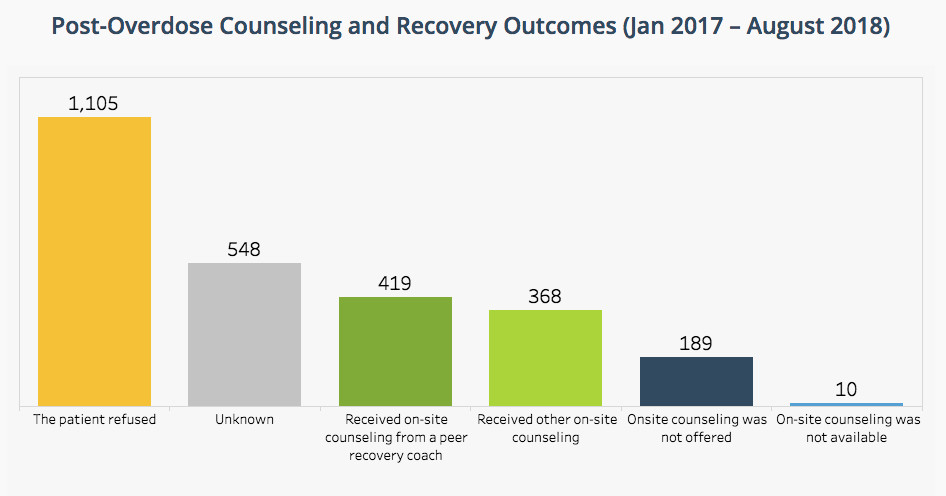

The numbers compiled and posted on the PreventOverdose RI website, looking at the outcomes for post-overdose counseling and recovery in Rhode Island at hospital ERs, from January 2017 through August of 2018, suggest there may be a different story to tell: Approximately 70 percent of the 2,629 post overdose patients [1,105 refused, 548 were unknown, and 189 had no onsite counseling offered] did not receive any counseling, while 16 percent [419] received onsite counseling from peer recovery coaches and 12 percent [368] received other onsite counseling.

Translated, the larger problem identified is what appears to be the ongoing resistance to counseling by patients recovering from a drug overdose in an ER setting. What that tells us, it seems, reinforces what many folks in the recovery community have been saying for years: the window that opens and closes for patients to seek help is often unpredictable; it requires the need to recognize that there are many places where there can be open doors to those seeking – and receiving – help, not just in an ER setting.

Measuring efficacy in a clinical trial, in an either/or comparison, social worker vs. a peer recovery coach, seems to create a competitive, rather than collaborative approach to a broader public health crisis around the diseases of despair – alcohol, suicide and drugs. Both interventions may have value; both may complement each other.

Or, to put it another way, rewritten news releases are much like reading truncated police reports or abbreviated obituaries in the local weekly: so much of the story does not seem to get told. Clinical trials may be the gold standard for academic researchers, but their actual relevance to what is happening in the community and on the streets may have limited, circumscribed value, in real time.

Perhaps a better topic for research would be to look at the differences in approaches in treatment and counseling between men and women, as a way of understanding how best to overcome resistance to counseling for patients after an overdose in the ER.

PROVIDENCE – There are times in covering the opioid overdose epidemic in Rhode Island when it feels as if, in my reporter’s role as ConvergenceRI, I have fallen into a time warp and somehow become immersed in a Raymond Chandler crime noir novel, taking on a role similar to that of Chandler’s fictional private detective, Philip Marlowe, attempting to ferret out the facts despite the numbing white noise machines of the powers that be that always seem to be operating on full volume.

On Friday, Oct. 12, Brown University announced that, in somewhat breathless prose: “Researchers from Brown University and Rhode Island Hospital have been at the forefront of battling the opioid epidemic in Rhode Island, and a new $800,000 grant from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation will help them to keep up the fight.”

First question: What is the mission of the Laura and John Arnold Foundation? What previous grant “investments” have they made in Rhode Island? John Arnold is a billionaire hedge fund manager and former Enron executive from Houston, Texas, who, with his wife, Laura, have made hundreds of millions of dollars in investments through their foundation in support of charter schools and entities involved in the corporate education reform industry.

The Arnolds, apparent proponents of doing away with public employee pensions, also donated as much as $500,000 to Engage Rhode Island, an advocacy group supporting pension reform efforts in the Ocean State.

The Arnold Foundation also donated $3 million in 2015 to create the Rhode Island Policy Innovative Policy Lab to work with policymakers in Rhode Island to help state agencies develop “evidence-based” policies to better serve Rhode Island families. What have been the results of that engagement to date?

Second question: Would academic researchers themselves – such as Dr. Jody Rich, Traci Green, Ph.D., and Brandon Marshall, Ph.D. – all of whom are expert consultants to the Governor’s Task Force on Overdose Prevention and Intervention – prefer to position their work as part of a collaborative team effort, rather than drawing specific attention to themselves or their institutions?

Positioning the academic researchers and clinicians from Brown and Rhode Island Hospital as being at the “forefront” of battling the opioid epidemic in Rhode Island can certainly be argued to be both true and accurate.

The three researchers will be featured as part of a panel discussion on Tuesday, Oct. 23, entitled: “Frontlines of the Opioid Crisis: Innovative Science-Based Solutions,” hosted by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and Brown University.

But, when thinking about someone who is actually on the frontlines of the opioid crisis, for ConvergenceRI, that conjures up Colleen Daley Ndoye, the executive director of Project Weber/RENEW.

Her community agency, a peer-based harm reduction and recovery services program for at-risk people in Rhode Island, including former sex trade workers, has just been awarded a $2.5 million, five-year federal grant from SAMHSA [the Substance Abuse, Mental Health Services Administration], in partnership with the R.I. Public Health Institute, to focus on substance abuse treatment for high-risk HIV negative Rhode Islanders, focusing on Black and Latino men who have sex with men. Why not include her as a presenter on the panel? The work underway that she is directing certainly fits the definition of science-based solutions?

Frontlines? Forefront? Who chooses these descriptors?

Third question: Why were the folks who run Anchor ED, under the direction of The Providence Center, a division of Care New England, not provided any bandwidth in the news release?

The apparent cheerleading on behalf of Lifespan’s Rhode Island Hospital emergency department and Brown School of Public Health seemed a bit odd, given that the program to be studied – the peer-based recovery intervention – was developed as an innovative program by the Anchor Community Recovery Center, called Anchor ED.

The numbers provided to ConvergenceRI by Deb Dettor, director of Recovery Support Services at Anchor Recovery Community Center, point to a different reality than the one being examined as part of the new clinical study funded by the Arnold Foundation:

For instance, in 2017, the Anchor MORE program [Mobile Outreach Recovery Efforts], which deploys peer recovery coaches to shelters, soup kitchens, bus stations and other geographic areas of the state that lack recovery supports, achieved impressive results through the work of six peer recovery coaches, including:

• 10,041 one-on-one conversations with people in the community

• 1,171 referrals for health care and basic needs

• 1,369 people transported to detox or residential treatment

• 4,135 kits of life-saving medication Naloxone distributed

The expansion of the “peer recovery coaching” model beyond the emergency room by Anchor MORE appears to be a more nimble effort to reach people where they are.

The fourth question: Do the parameters of the clinical study preclude asking a far more pertinent question, whether or not the new Centers of Excellence created at Rhode Island hospitals have resulted in an increase in the number of patients receiving services?

The Oct. 12 news release from Brown continued: “Under the terms of the research grant, the researchers are to conduct the first randomized controlled trial of a peer-based recovery intervention for patients at high risk of overdose.”

Dr. Francesca Beaudoin, a principal investigator on the grant and an emergency room department physician at Rhode Island Hospital as well as a Brown faculty member, was quoted as saying: “Randomized controlled trials are really the gold standard for making evidence-based decisions. Our new trial is the first randomized controlled trial of a peer-led recovery intervention for opioid use disorders in the U.S.”

ConvergenceRI, pursuing answers in the old-fashioned approach of traditional reporting – similar in nature to the kind of detective work undertaken by Chandler’s fictional detective, Philip Marlowe – began to make inquiries about the new study.

Old-fashioned, shoe leather reporting

The first call that ConvergenceRI made was to Mollie Rappe, Ph.D., the new Life Sciences writer at Brown University, who joined the school’s communications team about two weeks ago, replacing David Orenstein, who left in December of 2017 to take a job at MIT. Rappe explained that she was a molecular biology physicist, who had most recently worked at Sandia National Laboratory in New Mexico.

The conversation began on an awkward note: Rappe was unfamiliar with who I was and said she had never heard of ConvergenceRI, saying that ConvergenceRI was not part of her news media outreach list, and that she had received no instructions from Orenstein regarding my work. [Which was surprising, given that Orenstein, who had worked closely with ConvergenceRI since its launch in 2013, had told ConvergenceRI that he had specifically left instructions to his successor about the value of working with me. So it goes.]

Rappe then seemed somewhat put off by my question about the source of funding for the study, the Arnold Foundation, saying I should contact them directly. She was also resistant, if that is the right phrase, to my questions challenging the hypothesis of the study: whether the comparison between social workers vs. peer recovery coaches in an emergency room setting was the best way to determine the value of peer recovery coaching.

When I tried to explain how the peer recovery coaching initiative had begun in 2014 as an innovative solution by members of the recovery community to address what they saw as a gap in clinical care, the conversation floundered further, because it seemed that I was talking about ancient history.

I also raised the question about the differences in reimbursement and whether that should be a clear denominator in the clinical study: what an embedded social worker got paid vs. what a peer recovery coach got paid, related to value and outcomes.

[Recognizing that the conversation had veered off course, which was “my bad,” in large part because I kept questioning the study’s hypothesis, putting Rappe on the defensive, I suggested that we find time for a conversation over a cup of coffee at Olga’s, as an opportunity to get better acquainted, realizing that our initial encounter had not gone well. Stay tuned.]

Rereading the files

The next step in the shoe leather approach was to take a step back in time and reread the stories I had written in 2014 and 2015, to refresh my own memory about the history of peer recovery coaches and their introduction to hospital emergency rooms.

The peer recovery coach program began as a pilot program, a kind of innovative, improvisational riff, espoused by the late Jim Gillen and his compatriot, Holly Cekala, in June of 2014, as a way to develop a different way of intervening with patients following a drug overdose. [Some discussion involved Becky Boss, in her role at the R.I. Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals.]

The idea was straightforward: those in recovery could help those who were still under the influence find the path toward recovery.

Here is what ConvergenceRI reported in February of 2015, in the story, “Recovery intervention at emergency rooms by the numbers.” [See link to the story below.]

In June of 2014, with Rhode Island in the grips of an epidemic of accidental overdose deaths, a new innovative program was developed to connect overdose patients in emergency rooms with certified recovery coaches at Rhode Island hospitals, in order to provide the support needed to link patients to treatment and recovery.

The effort, called Anchor ED, was an initiative managed by the Anchor Recovery Community Center, a program of the Providence Center.

Jim Gillen, director of Recovery Support Services at the Providence Center, and Holly Cekala, the manager of Anchor ED, coordinated the new initiative.

It placed certified peer recovery coaches on call, every weekend from 8 p.m. Friday night through 8 a.m. Monday morning at participating hospitals. Weekends had been identified as a time when frequent overdoses occurred.

The first hospital to introduce this program was Kent Hospital in July of 2014. Since then, Rhode Island Hospital [on Aug. 29, 2014], Miriam Hospital, Memorial Hospital and Newport Hospital have joined the effort.

The goal of placing on-call recovery coaches in hospital emergency rooms was to break the cycle of overdose and addiction, linking patients to treatment and recovery resources. The recovery coaches also provided education on overdose prevention, including the use of Naloxone [or Narcan], as well as connecting patients and their families to support services after discharge.

The story in ConvergenceRI then went on to detail the effectiveness of the program in saving lives and saving money, according to a new report published in February of 2015:

A new report, “Anchor ED: A Care and Treatment Approach to Opioid Addictions, written by Holly Cekala and Jen Palo,” was released on Monday, Feb. 9, detailing the efforts.

Seven months after the program began, 112 survivors of overdoses in hospital emergency rooms were seen and 88 percent of them engaged in recovery supports.

To put those numbers in some perspective, in 2014, a total 232 people died of accidental overdoses in Rhode Island.

The report also broke down the demographics, ethnic diversity and ages of the patients that received recovery coaching and support.

There were 79 men and 33 women; 75 percent were White, 18 percent were Latino/Hispanic, 3 percent were African American, 2 percent were Pacific Islander, and 2 percent were more than one race.

The story continued, documenting episodes of prior treatment and prior overdoses and the chronic nature of the affliction:

The numbers also reinforced the difficulty in treating the chronic nature of the disease of addiction.

When survivors were asked in they had been in treatment in the prior year, one-third, or 38 out of 112 said yes.

Survivors were also asked if they had overdosed before in the last 12 months; 38 percent, or 42 out of the 112 survivors, said that they had had a prior overdose, according to the report. Some reported multiple overdoses, ranging from two to as many as 16.

The peer recovery coach’s viewpoint

The next “expert” ConvergenceRI sought out was Jonathan Goyer, a member of the Governor’s Task Force on Overdose Prevention and Intervention, the director of the Anchor MORE program [Mobile Outreach Recovery Efforts], a peer recovery coach, and a survivor in long-term recovery.

Goyer, in his truth-telling fashion, wrote in response to an email from ConvergenceRI that he did not know the full extent of the clinical study. But, he said, “I am glad to see peer recovery coaches getting any evaluation on this level. The work that peers do is of unprecedented value; however the supported research opportunities behind it are typically slim to none.”

In terms of documenting the value of the work by peer recovery coaches, Goyer continued: “Recovery coaches touch the lives of thousands of Rhode Islanders a year, and account for [more than] 50 percent of the state’s total [naloxone] trainings and distribution for the past three years.” [Once again, in 2017, the MORE program that Goyer directs distributed 4,135 naloxone kits.]

In a follow-up email to ConvergenceRI, continuing the conversation, Goyer wrote: “Is comparing a peer to a social worker effective? I’m not sure. I will say that I don’t know if it is the ‘right’ thing to do – but it certainly is not the ‘wrong’ thing to do.”

Goyer said that he was unsure what the “metrics would be collected in this study, but framed his response by saying: “The entire country has failed miserably in creating successful metrics for recovery – ones that are honored, recognized and embraced by the medical community.” At this time, Goyer added, “I have nothing telling me that this study will be any different.”

The R.I. Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals, Goyer continued, has collected some vital information on cost-savings for individuals seen by a peer [recovery coach] in the [hospital] ED. “So, if money savings are an ideal outcome, we can determine that,” Goyer said. He also mentioned that the R.I. Executive Office of Health and Human Services is currently working on re-configuring metrics around the new version of the strategic plan, including recovery.

In conclusion, Goyer wrote: “I view this study as a win, in that it brings more attention, more light onto solutions. I’m a man who likes to live in solutions.” But, he added: “Your questions are valid, and I hope you are able to track down some further insights/answers.”

Goyer recommended that ConvergenceRI contact Deb Dettor, the director of Recovery Support Services at Anchor Recovery Community Center, for further comment.

The agency director’s perspective

As the person responsible for overseeing and coordinating the peer recovery coach initiative at the Anchor Recovery Community Center, Dettor offered her perspective on the new clinical research study. [In the news release, Anchor Recovery Community Center is listed as a partner in the study.]

“I am not in a position to try to clarify the study design – that is a question for the research team,” Dettor said, adding: “We are very interested in studying the effectiveness of ED Recovery Coaching interventions and need good researchers who can do this.”

When asked about the data from the PreventOverdose RI website, and the large number of patients post-overdose who refused counseling opportunities, Detter said: “I don’t know that the PreventOverdose RI tracks referral rates in the same way [that we] do, so I cannot comment on their numbers.”

She continued: “We track the people who agree to see a recovery coach and who we engage; they are tracking the larger population of folks who show up at the ED.”

Dettor further explained the methodology that Anchor ED uses as part of its peer recovery coaching initiative: “For every onsite ED visit, recovery coaches offer every patient a menu of recovery support options, which includes treatment; the only thing we can track is whether the person agrees to the referral or not.

Our intervention, Dettor continued, “ends at the ED, unless the person signs up to receive ongoing recovery coaching through Anchor. My understanding of this study is that they will follow people as they leave the ED and track where they go from there – do they make it to treatment or recovery support services?” This data, Dettor said, will gather additional information beyond the ED doors.

Dettor provided the statistics for 2017 from the Anchor ED program as a way of detailing how the initiative tracks patient referrals and acceptance rates. The 22 peer recovery coaches employed by Anchor ED:

• Responded to 1,750 ED calls

• Had, on average, a 34-minute response time to calls from the ED

• 87.6 percent of individuals seen peer recovery coaches from Anchor ED agreed to treatment and/or recovery referral

• Provided services 24 hours a day, 7 days a week at all hospitals in Rhode Island.

In a follow-up email, Dettor wrote: “I am finally reading the Oct. 15 post [in ConvergenceRI, ‘Task force on ODs maps out strategic plan through 2021.’] Thank you for elevating this to having an important status and for your writing!”

Asking questions, not getting answers

ConvergenceRI did reach out to a number of other folks in working in state government in an attempt to get their response to questions about the study, including Tom Coderre, senior advisor to Gov. Gina Raimondo, who was quoted in the news release from Brown University.

In the news release, Coderre said: “Peer recovery support programs are a vital part of our fight against the overdose epidemic in Rhode Island. We hope that this randomized controlled trial confirms these programs are effective at connecting people with lifesaving resources, and anticipate the results will encourage other states to undertake similar programs.”

However, Coderre told ConvergenceRI that he was not the right person to answer questions about the study, and suggested that ConvergenceRI reach out to Brown’s Brandon Marshall for comment, who is the principal investigator for the study.

ConvergenceRI also reached out to the R.I. Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities, and Hospitals. The agency spokeswoman suggested that her agency was not the right place to go to answer questions, and, like Coderre, suggested that ConvergenceRI talk with Brandon Marshall. BHDDH was listed as one of the partners in the study, according to the news release, along with Lifespan and the R.I. Department of Health.

ConvergenceRI did try to reach out to Marshall but has not yet received a response. Here is what Marshal said in the news release: “We’re looking at two promising interventions: social workers, who have specific clinical training and expertise and are the standard of care, and the peer recovery support specialists, who are unique in that they bring their life experiences with addiction and follow up with the patients, often several months after discharge from the emergency department.”

Due diligence

The clinical study will be completed in four years, in 2022, eight years after peer recovery coaching was begun in Rhode Island as an innovative, improvised solution to the apparent clinical failure in hospital emergency rooms.