Sketching in the landscapes of despair in RI

Presentation by sociologist Shannon Monnat at RIC was “one of the most valuable things I have seen in a long time,” according to Sen. Joshua Miller

As Rhode Island’s demographics change, as we become older and at the same time, more diverse, the way in which we define community becomes even more important as a function of economic development. As Sen. Josh Miller said, quoting Dr. Peter Simon, at Shannon Monnat’s talk, “Remember: health insurance is not health care.”

PROVIDENCE – After months of procrastination, President Donald Trump held a photo op on Oct. 26 to declare the obvious: the opioid drug epidemic is a public health emergency, in a kind of Homer Simpson “doh” moment.

Trump fell short of declaring the epidemic that is killing some 100 Americans a day to be a national emergency; Trump also failed to commit any additional federal money to the task ahead. Instead, the President said that the Public Health Emergency Fund, which has just $57,000 in its coffers, would be the source for federal resources.

The next day, Trump sent outgoing N.J. Gov. Chris Christie, the chair of Trump’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis, to shill for him on the morning TV news shows.

In a bait-and switch political maneuver, Christie attempted to put the onus on Democrats in Congress, saying it was up to Congress to appropriate the money. Christie, who took his family to the shore this summer when a state budget impasse closed that same New Jersey beach to the public, said he expected there would be proposals to expand Medicaid waivers to include more money for medication assisted treatment.

Some of Rhode Island’s elected leaders were quick to respond. “The opioid crisis is a national emergency that requires urgent care, attention, and resources. The President’s response has been underwhelming [emphasis added],” said Sen. Jack Reed. “Today’s announcement fits a pattern for President Trump: lots of bluster, little action, no solutions, and punt the problem to someone else.”

Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse said: “To fight this emergency in earnest, we need more than declarations; we need full funding behind the Comprehensive Addition and Recovery Act which Congress passed last year.”

R.I. Gov. Gina Raimondo said: “President Trump’s announcement today falls short and shows that he does not fully understand the scope and real-life impact that this crisis has had on Rhode Islanders and Americans who have been directly touched by addiction and overdose.” [None of the recently announced Republican candidates seeking to challenge Raimondo for re-election in 2018 had anything to say about the matter.]

Perhaps the most important response, however, was by sociologist Shannon Monnat, in her talk at Rhode Island College on Oct. 27, “Landscapes of Despair: A Demographer’s Take on Drug, Alcohol and Suicide Mortality.” Monnat laid bare the reality of the current epidemic and its relationship to economic decline, cynicism, anxiety, stagnation and slippage – and the culture of chronic loneliness.

Monnat did this by presenting the evidence-based analysis of what were the demographics around the epidemic: who is dying by age; where they are dying, broken down by county; and what they are dying from [connecting alcohol and suicide with drug mortality as well as the specific drugs].

The demographic evidence produced by Monnat made it clear that leaving out the economic equation would be a prescription for failure.

“We can’t Narcan our way out of this; we can’t treat our way out of this. The problem is bigger than opioids, and there is no single solution,” Monnat told audience of about 70 who gathered at Alger Hall.

“An individual’s opportunities, choices, behaviors, health and well being do not manifest in a vacuum,” Monnat concluded. “They exist within the context of larger social structures: family, the economy, educational institutions, health care systems, political systems, and community.”

Most valuable

The response panel, consisting of some of the more knowledgeable people in Rhode Island when it comes to addressing the epidemic of addition and overdose deaths, were blown away by what Monnat had to say.

State Sen. Joshua Miller, chair of the Senate Health and Human Services Committee, and a member of the Governor’s Task Force on Overdose Prevention and Intervention, called Monnat’s presentation “one of the most valuable things I have seen in a long time.”

Over and over again, Miller continued, most presentations stop halfway – focusing on the origins of the epidemic, tied to the marketing of prescription painkillers by pharmaceutical companies and distributors and the prescription practices of physicians to treat pain.

“We don’t see the other half,” Miller said. “It’s really, really, really important for people who are working on this to know that there is a structure” to what is occurring.

Absolutely

Angela Ankoma, the chief of Minority Health at the R.I. Department of Health, who will soon transition to a new job at United Way of Rhode Island, said that Monnat’s presentation had “absolutely” changed her understanding of the opioid epidemic.

Much of Ankoma’s work at the Department of Health has been focused on developing health equity zones to address community-based responses to social, economic and health disparities, connecting health equities to social environments. From her own personal history, she said she had witnessed how the crack epidemic two decades ago had “decimated my neighborhood.”

As a result of Monnat’s talk, Ankoma said she saw how important it was to break down the silos that exist at the state health agency, connecting the work being done on health equity with the work being done on overdose prevention. “We need to rethink how we are approaching this work,” she said.

Despair is real

For Holly Cekala, the former director of RICARES who was instrumental in developing the peer recovery coaching initiative in Rhode Island with the late Jim Gillen, the diseases of despair are intimate and real, not academic. “I’m deeply affected by addiction and the diseases of despair,” she said.

Cekala, a person in long-term recovery and a graduate of Rhode Island College, currently works as a consultant for Harmony Health Solutions in New Hampshire.

The first person she buried from an overdose was her own mother, Cekala told the audience, soon followed by her brother, then her brother’s daughter.

All too often, Cekala said, the message driven home to people is this: “Your life, and my life, doesn’t matter.” But, she countered, “They matter; they do matter.”

When Cekala came out of prison, she said she filled out 55 applications to try and find a place to live. “No one would give me a home; no one would give me a job,” she said. “The despair is real.”

The challenge, Cekala continued, is to help find those in recovery and those coming out of prison meaningful work, getting them skills. More than medication assisted treatment, Cekala said, people coming out of jail need jobs.

Battling the contagion

For Traci Green, an epidemiologist working as an adjunct associate professor of emergency medicine and epidemiology at the medical school at Brown University, who is also a member of the Governor’s Task Force on Overdose Prevention and Intervention, she said she found similarities in her work and Monnat’s work, connecting sociology and epidemiology.

Green drew the distinction between what she called the infectious and chronic aspects of addiction.

The infectious nature of the opioid overdose epidemic, Green said, is a contagion, a contamination; it is an infection that changes rapidly. The goal needs to be “to contain it as quickly as you can.”

From the chronic perspective, incarceration is a huge risk factor, no matter where you go in the world, Green continued. And, it promises to get worse with a renewed focus on criminalization of drug policies [under the new Trump administration], she said.

Green cited incarceration, racial and structural violence, unemployment, poverty, education and gender equity, especially domestic violence, as components of the “chronic” aspect of the diseases of despair.

“Sex workers are becoming a more important component of heroin and fentanyl abuse,” she said.

In turn, Green urged that the businesses embrace what she termed “our recovery workforce” and investment in a recovery workforce and a treatment workforce.

Take aways

Monnat’s presentation included important details that are not often discussed as part of the conversation around the opioid addiction epidemic.

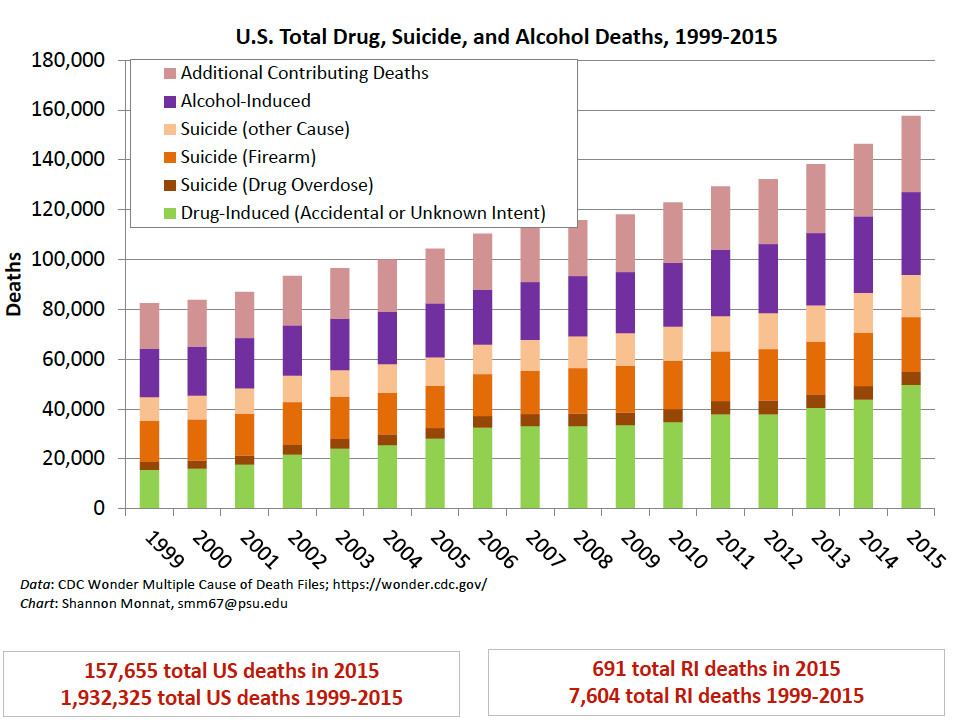

• In her slide detailing total drug, alcohol and suicide deaths in the U.S. between 1999-2015, Monnat broke out six categories: drug induced; suicide from drug overdose; suicide from firearms; suicide from other causes; alcohol induced; and additional contributing deaths.

• In Rhode Island, there were 691 total deaths in 2015 from alcohol, drugs and suicide, according to Monnat’s analysis, as compared to the total of 290 confirmed overdose deaths from drugs in 2015. Translated, the deaths of despair in Rhode Island were more than double the number of drug overdose deaths.

• Monnat’s analysis also found that there were substantial demographic variations in mortality for drugs, alcohol and suicide by race, sex and age. In Rhode Island, for instance, Monnat found that 59.8 percent of all white adults, male and female, between the ages of 25-34, died from alcohol, suicide or drugs during 2010-2014, the highest such morality rate in the nation.

• In terms of measuring the pain prescription surge, Monnat found that between 2000 and 2010, approximately 25 percent of all non-cancer patients who received Rx opioids for oxycodone, hydrocodone, morphine, methadone, hydromorphone and fentanyl had long-term struggles with addiction.

• The counties in the U.S. with more economic, family and social distress had the highest rates of mortality for alcohol, suicide and drugs, during 2006-2015, broken down by poverty rate, disability rate, percent unemployed, uninsured rate, single parent families, and the percentage without a four-year college degree.

In her talk, Monnat discussed some of the reasons why non-college educated whites are far less positive about their relative standard of living than blacks or Hispanics: the fact that for many whites, there was a feeling that they were not going to be doing better than their parents economically.

Monnat also quoted Sam Quinones from his book, Dream Land, who said: “This was not new; it had been happening for 15 years. And there was more to it than drugs. This scourge was…connected to the conflation of big forces: economics and marketing, poverty and prosperity. Forgotten places of America acted like the canaries in those now-shuttered Appalachian coal mines. Just no one in the country listened much until more respectable types sounded the alarm.”

As an example, in Lucerne County, Penn., where the city of Wilkes Barre is located, Monnat tracked how manufacturing jobs had declined by 55 percent since 1980, from 42,000 to 19,000, while median household income had remained stagnant. In turn, there was a chronic out-migration of young adults. At the same time, in the last 15 years, drug overdoses tripled and suicides by causes other than drugs doubled.