In America, all we do is work, but for whom? And, for what?

Reflections on honoring and capturing the value in what we do for a living

As The New York Times recently attempted to rectify, many famous women and the legacy of their accomplishments were often overlooked, with no obituaries published, as part of the continuation of the “great man” theory of history.

The best read sections of newspapers, assuming that people still read, follow a predictable pattern of behavior: first are police and court reports, second are obituaries, third are letters to the editor, fourth are comics, fifth are sports. Sometimes front-page stories will interrupt the pattern of reading behavior, if there is a major tragedy or disaster.

The truth: sex sells; violence sells; outrage sells; gossip sells, mayhem and anxiety sells. For the most part, people prefer to be lied to, rather than hear the truth. And, they like to dish the dirt about others.

Still, I am thankful this Labor Day for all the people who have had the trust and the courage to share their stories with me, in the belief that I would tell them, honestly and accurately, detailing their travails and their dreams. I am thankful for all the opportunities to sit down and talk with people, one on one, in conversations, to the people who have allowed me to ask questions.

And, I am thankful for all the readers and subscribers to ConvergenceRI, who continue to find great value in the contents of what is written and shared.

The most important “product,” the most important possession we have, is our own personal stories, and the sharing of such stories becomes the key ingredient in the human endeavor that defines our humanity and our engaged community of refugees, immigrants and survivors.

PROVIDENCE – In what is becoming a Labor Day tradition, I am sharing some reflections about the nature of hard work, determination and lessons earned along the way.

In 2017, I wrote about the dark underside of working in kitchens, the fall back when my career as a young writer faltered, becoming a denizen of the down-and-out netherworld once chronicled by George Orwell. [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “A personal meditation on the nature of work on Labor Day 2017.”]

The cook strung out on speed I witnessed pulling an unloaded pistol out of brown paper bag and, as an unfunny joke, putting it against the head of another cook and pulling the trigger, was not a tale I often shared.

Or, what happened when I took up the cause of a Nigerian dishwasher on the dayshift, married, with two kids, working a second job at Burger King at nights, who objected when the head cook kept referring to him as a member of his kitchen boys. “I am not a boy.”

In 2018, I wrote about the experiences of my mother who, as a middle-aged social worker, became shop steward of her union and led a strike at age 49, sharing my own experiences in navigating around the shoals of treacherous bosses. [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “Labor Day blues.”]

This year, I am writing how the immigrant experience shaped the life of one of my grandfathers, my mother’s father, and provided me with some important economic history lessons about the 20th century – though certainly not the ones he had intended.

The lessons my grandfather sought to pass along to his 10 grandchildren about the meaning to be found in a life dedicated to hard work on the road to success promoted the myth about his life journey as the self-made man, conforming to the dominant narrative that hard work could somehow set you free.

While his was a remarkable story, I have always found much more credence in the Hoyt Axton lyrics: What to do you get from working your fingers to the bone? Boney fingers.

Which doesn’t mean I do not place great value in working hard and persevering, which are, as a writer and a reporter, important traits and attributes of our profession. But the metrics in how we measure the value of our work need to reflect much more than just the bottom line about how much “wealth” and prestige we accumulate along the way.

Born on Christmas Day

My grandfather, born Josip Davidowich, in Iasi, Romania, on Dec. 25, 1884, arrived in America in 1900, when he was 15 years old, one of more than 1 million immigrants to enter the U.S. that year.

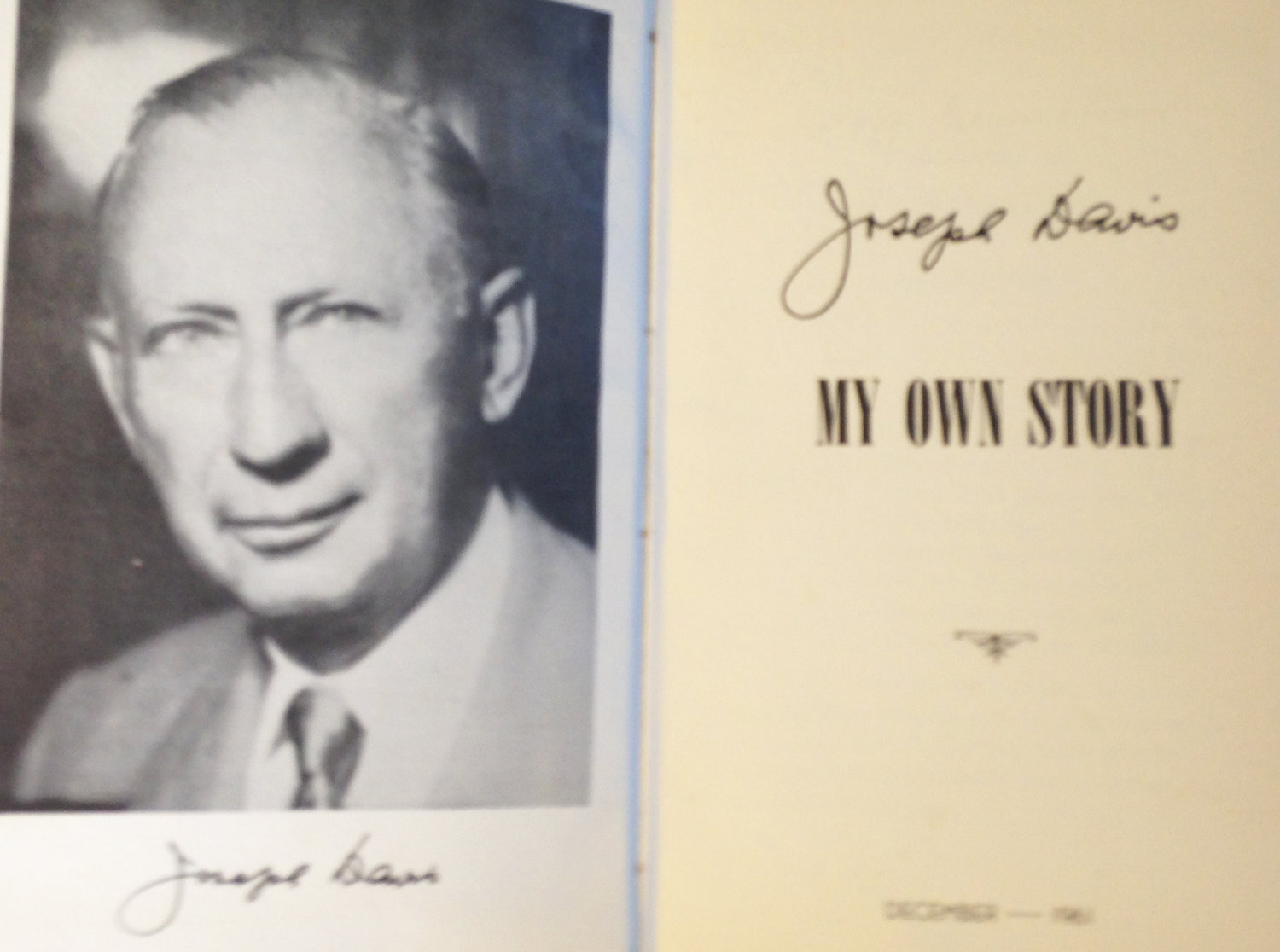

What I know of his story is mostly gleaned from an autobiography he wrote and published, “My Own Story,” in 1961, the year he turned 77. In rereading his story recently, I found it to be an illuminating tale, but not necessarily in the way he envisioned it would be.

The oldest of five children, he fled Romania to arrive in New York City, as he described it, “practically penniless, badly battered by a rough Atlantic crossing.” His transport had been arranged secretly through B’nai Brith, traveling by train across Europe through Vienna, Brussels, Paris and then Le Havre, where he boarded the S.S. Champagne, traveling 11 days in steerage. The money sewn into his underwear was one of the few things not stolen from him.

The compelling reason why he left Romania, as he detailed in his story, had a lot to do with organized government pogroms against the Jews, in particular, one on May 16, 1897, when mobs threw rocks and stones at his home. He also sought to avoid military service in Romania, a terrible fate for any Jew. As a teenager, he became a protector of Jewish families who gathered water from a public fountain, punishing ruffians who attacked the Jews, hammering them with a metal rod, until the police intervened.

His father, a metal worker, had taught his son the basics of the trade, and after arriving in America, my grandfather survived working a series of jobs in manufacturing, always clever with his hands.

His story very much conformed to the myth of the penniless immigrant who made good, who would become one of the plastics pioneers in the U.S.

Along the way he struggled as an itinerant, hardscrabble laborer: he worked for three months on the Panama Canal; he worked for various manufacturing companies in New York City, in Newburgh, N.Y., and in Philadelphia. In some cases, he found work as a strikebreaker, working for a detective agency as a spy on other workers. His ethics were situational, based on economic survival. [That the daughter of a scab grew up to be a shop steward of her union, leading a strike at age 49, is a testament to the fallacy in the belief in life as a predetermined fate.]

Skilled with his hands, my grandfather created vending machines; he designed tricks for the magician Harry Houdini; he even designed a way to project the latest election results on screens on election night in New York City. He invented a number of devices, including a vacuum cleaner and a vacuum clothes washer, and even a three-in-one garden set.

The various business ventures were successful enough for him to arrange for the rest of his family in Romania to come to America – his father, his mother, three sisters and a brother. All their lives would have been extinguished, no doubt, by the Nazi onslaught during World War II, if they had stayed.

My grandfather went on to build his own successful plastics company, Joseph Davis Plastics in Kearny, N.J., which ended up being sold to a larger company, Richardson, in the late 1960s, which then plundered the cash assets built up by the firm, leading to an eventual bankruptcy. If my grandfather’s tale as an immigrant success story defined the myth of the U.S. as the land of opportunity, the liquidation of his company, a victim of the engulf-and-devour corporate raiding, presaged the current world of the 21st century we live in, built upon debt financing, venture capital, and hedge fund investors.

A landscape pencil drawing my grandfather had done of the company’s location on the edge of the Jersey Meadowlands, which hung as a testament to his success in his den, contained a handwritten note, added a year or two before he died at the age of 99, a coda of bitterness, saying that the firm had been destroyed by the avarice and greed of a few individuals. So it goes.

Reading my grandfather’s story again made me realize how much was missing from his tale: how would my grandmother have told her story, in her own words, if given the chance and the opportunity? How would her story have differed from my grandfather’s own tale of self-importance? What would have been her perspective about the story of their courtship?

Lessons in survival: what tribe are you?

In 1973, Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray released his film, “Distant Thunder,” which documented the man-made famine, deliberately caused by the British during World War II, in which more than 5 million Bengalis starved to death, far removed from the ongoing conflagration, which had, as the name of the film captured, occurred as a distant thunder in their lives.

It is a story rarely told or mentioned in the European-centric histories of the conflict. In a sea of wanton death and cruelty, when enormous factories of death were built upon the creed of racial purity to promote fascistic empires and murder millions, with brutal sacrifices made on battlefields across the globe to preserve Western democracy, the Bengal famine remains a mostly untold story, an afterthought, a footnote, outside the dominant narrative. It does not make it any less real or tragic.

Immigration today is once again a hot-button issue, in a world where the emotional appeal of right-wing populism has attempted anew to redefine the purity of race, religion and creed by demonizing “the other.” It is a story as old as human history, promoting bowing down to the false gods of scarcity in the name of conquest.

Despite what Trump apologists say about reinterpreting the words of the poem on the Statue of Liberty to give us your tired and your poor and those “who can stand on their own two feet,” no one stands alone on their own two feet without support from a network of family, friends, community and indeed, the kindness of strangers. No one.

Unless one is descended from a Native American tribe, we are all children, grandchildren, great grandchildren or great great grandchildren of immigrants. Most arrived on this North American landmass in pursuit of a better future. Many of our grandparents have similar stories to tell as the one told by my grandfather; it is a shared, common history.

Many of the original colonists sought to escape the perils of an intolerant Europe; many others arrived in chains, under the cruel yoke of colonialism, slavery and indentured servitude. Both parallel narratives are true.

Still others arrived with the “property” rights bestowed upon them by their kings and queens to rape, to plunder, to exploit, to ravage, to dig for riches. The newly found “riches” of the New World soon became the fuel of corporate empires, from cotton and rum to whale oil and petroleum, all built upon the backs of those who toiled.

What gets left out of the narrative is, upon reflection, often more important that what gets put into the myth about achieving success through hard work and sacrifice, on the assembly line of products and services, on the highway of branding and repackaging and selling. But how do we ever learn about those stories, if we have been “conditioned” not to hear or see them?

In dreams begin responsibilities

As a writer, reporter, investigative journalist, editor, executive editor, publisher, scriptwriter, ghostwriter, head of a nascent TV production company, communications director, and now, a digital platform entrepreneur, I have always been struck by the ephemeral nature of the work product created.

Much like the “disappearing” company created by my grandfather, more often than not, the tangible evidence of my work product has also disappeared, swallowed up by the shifting winds of corporate ownership, technology changes, and, yes, greed. I owned the byline, not the product. My historical records have become only what can be found in a Google search, however distorted and incomplete those are.

A decade ago, in 2010, I attempted to digitize many of the stories I had written, as a way preserving an archive of my work. In the introduction to that still unpublished work, I wrote: “I never followed a traditional path, and I often chose to live on the outskirts of the traditional world.”

The phrase, “outskirts of the traditional world,” referenced my reporting on the impact of mercury poisoning on the Cree in northwestern Quebec, and how their lives had been disrupted when fish, a prime protein source during the summer months, had become contaminated by mercury from industrial pollution and were now unsafe to eat. [The story was published in The New York Times Magazine in 1979.]

As I wrote in the introduction to the unpublished collection of my work, “I had never imagined that I would bear witness to the dissolution of a native culture in North America in the 20th century.”

A short five decades later after my initial reporting on the Cree, we have all become refugees, living on the outskirts of an ever-shrinking modern world, witnessing the Earth on its last long exhale, skating away on thin ice before the apocalypse of climate change.

The profession of storytelling

Journalism is not a healthy profession, no matter how much it is glorified. “The incessant demands of journalism – there’s always a deadline, there’s always a crisis – are not conducive to living a long and healthy life or prospering in a relationship,” I had written in the introduction of my unpublished 2010 collection of journalism and prose.

I had also quoted an introduction that I had written to an unfinished novel, begun in 1982: “When people ask me what I do, I tell them that I’m a storyteller, weaving a thread of intimacy and intrigue to connect what has happened before us to what will happen after we are memories.”

In most of the numerous jobs I have held, I was always expected, much like professional athletes these days, to play hurt, to sacrifice myself, my body and my health to the greater good of the team and its owners, in the belief that my dedication would be rewarded – further on down the road, with the cash prizes held out like a brass ring on a merry-go-around that is always so tantalizing close and yet so far away.

Whether I worked for the straightest daily newspaper or the most alternative news weekly, for the most altruistic nonprofit or the most corrupt state agency, the mantra was a self-evident truth: workers were always to be exploited to the fullest extent of our talents, made to work long hours without adequate pay or benefits, and when on salary, never ever paid overtime.

Acknowledgements of those contributions, those efforts, always seem to get swept away in the “great man” theory of history and corporations, all too willingly championed by reporters – as if the decision to launch off-shore wind energy in Rhode Island belonged to the legacy of only one governor, ignoring the contributions of a generation of scientists and entrepreneurs and energy activists. Such purposeful distortions make it that much harder to break free of the dominant narrative that I believe is strangling our democracy.

What would the other side of the narrative look like or read like? When nurse Giovanna Todisco retired after 59 years of working as a nurse at Women & Infants Hospital, she praised not herself, but her colleagues, the other nurses, whom she said always had each other’s back, in their dedication to the profession of caring, of taking care of the patient.

The more interesting part of the story, told by her nursing colleagues at the celebration, was how, when President and CEO Dr. James Fanale announced that Care New England was pulling out of the merger negotiations with Lifespan and Brown University, there had been an outburst of joyful, spontaneous applause, which grew into a standing ovation.

In a recent off-the-record conversation with a business leader, my reporting about that standing ovation was discounted, saying even if there actually were relief on the part of some employees at Care New England on the breakup of merger talks with Lifespan, it could likely be attributed to the tribalism of different unions at the two facilities, or among managers fearing normal trepidation about a consolidation of some positions. It most certainly wasn’t related to what may be in the best interest of health care in the state of Rhode Island, the business leader insisted.

The question is: in the best interest of health care for whom? The patients? The nurses? The community? Who gets to decide on what is in their best interests?

For those who have become conditioned to hear, to listen to, and to promote the dominant narrative, when nurses speak up, when teachers speak up, when students speak up, when workers speak up, who will share their stories? Particularly if those stories do not fit into the dominant corporate agenda.