Everything you wanted to know about care transformation but were afraid to ask

Ten years after it began as a pilot program in 2008, the Care Transformation Collaborative-RI held its annual conference to chart out its next steps

WARWICK – The Care Transformation Collaborative of Rhode Island held its annual conference on Thursday, Nov. 1, at the Crowne Plaza, attracting several hundred participants in a full-day series of discussions around the topic: “Building Capacity for Comprehensive Primary Care.

In the last decade, CTC-RI, which began as a pilot program in 2008 to advance an all-payer, patient-centered medical home model for primary care delivery under the direction of former R.I. Health Insurance Commissioner Christopher Koller, has grown to become a dominant player in the delivery of health care services for primary care in Rhode Island, with approximately 350,000 Rhode Islanders receiving their primary care from CTC-RI practices.

The mantra of the conference was “better care, lower costs,” with opening perspectives offered by Debra Hurwitz, the executive director of CTC-RI, Marie Ganim, the current R.I. Health Insurance Commissioner, Marti Rosenberg, the project director of the State Innovation Model project in Rhode Island, and Randi Redmond Oster, founder and president of Help Me Health, a patient advocacy organization.

Who was attending the conference was, in many ways, as impressive as who was speaking: the participants were a veritable who’s who of health care reform in Rhode Island, which translated into a high level of discussion around policy issues at the 18 concurrent breakout sessions that were part of the conference.

For instance, there was Dr. Jeffrey Borkan, chair of Family Medicine at the Warren Alpert Medical School; Garry Bliss, the Accountable Entity program director for Care New England’s Integra ACO; Dr. Patricia Flanagan, co-director of PCMH-Kids, a patient centered medical home model for pediatric practices; Rick Brooks, head of Rhode Island’s Healthcare Workforce Transformation Initiative; Lynn Blanchette, Associate Dean, Rhode Island College School of Nursing; and Matthew Roman, chief operating officer of Thundermist Health Center, among others.

Translated, it was a high-level dialogue taking place around health care reform and care transformation, very high up on the policy mountain – but it was unclear how that would be integrated into the day-to-day realities of health care delivery.

For instance, as a way to translate policy into practice, ConvergenceRI made the suggestion that the conference next year might feature a flu shot clinic for participants, given the low rate of adults receiving flu vaccinations. “What a good idea!” Hurwitz responded.

Policy informs practice

The presentations and conversations were often a policy wonk’s delight. At the concurrent breakout session entitled, “Building Team Capacity: Utilizing Provider/RN Co-Visits, Pharmacy Technicians and Patient Navigators,” Wendy Chicoine, director of Clinical Education at the Providence Community Health Centers and an adjunct professor at Rhode Island College, identified what she called the missing aim of the Triple Aim: “improved clinical experience.”

The panelists talked about the need to build a team approach that integrated pharmacy technicians, nurses and patient navigators as part of the health care team interacting with patients, with examples of success of achieving such integration.

At another concurrent breakout session, entitled “Better Care and Lower Costs: Partnering in the Community To Meet Health Related Social Needs, Jeannine Casselman, talked about the kinds of legal interventions being practiced by MLPB as an advocate for patients who were “heading to the legal emergency room.”

Scott Hewitt, the community health team coordinator at Blackstone Valley Community Health Care, described the way that an interdisciplinary team functioned to develop solutions for complex patients involving social determinants of health as part of the Neighborhood Health Station in Central Falls.

Accountable entities in Rhode Island

Ever since the R.I. General Assembly enacted the reinventing Medicaid legislation in 2015, the cornerstone of the new law was the creation of a series of accountable entities for the managed Medicaid population, as a way to drive down costs and improve outcomes, based on population health management metrics.

Critics of the legislation to reinvent Medicaid pointed out that the effort would open up the revenue stream of Medicaid dollars to larger health systems beyond community health centers, including Prospect Health, Care New England and Coastal Medical, as well as to include Tufts Health Plan as a managed care organization, joining with Neighborhood Health Plan of Rhode Island and UnitedHealthcare. The question, yet to be answered, is this: will the larger health systems prove as adept and cost-effective as community health centers in providing primary health care for the often complex needs of Medicaid patients?

A second, more difficult question to answer is how population health will be defined: is it by the patient population served by the health care delivery entity, or by the neighborhood where the patients live?

More than three years after the law was enacted, with little fanfare or public relations hoopla, the certification of accountable entities and the approval of contracts with managed care organizations [health insurers] went into effect on Oct. 1, 2018.

There are six accountable entities certified by R.I. Executive Office of Health and Human Services. They include:

• Blackstone Valley Community Health Care

• Coastal Medical

• Integra Community Care Network [Care New Engalnd]

• Providence Community Health Care Centers

• Prospect Health Services of Rhode Island [CharterCARE]

• Integrated Health Partners, a collaboration of six different community health centers

Details about how exactly the accountable entities will be held accountable during the first year of operation still remain somewhat murky, to say the least. First, there are no accountable entities specifically targeted for Medicaid long-term care services, one of the principal cost drivers of state Medicaid expenditures.

Second, as part of the mechanism that will allow Medicaid dollars to flow to the accountable entities, each accountable entity must complete and file what is known as HSTP, or Health Services Transformation Plan, by April 1, 2019, according to sources.

Once the HTSP is filed, then the accountable entity can receive Medicaid payments for the next year, according to sources.

Translated, the new population health metrics stipulated under the accountable entities will not be enforced until April 1, 2020, as best as can be determined, given the lack of state transparency about the process. [ConvergenceRI would welcome Eric Beane, the director of the R.I. Executive Office of Health and Human Services, or Patrick Tigue, the director of the R.I. Medicaid office, to clarify the confusion about what is going on, on the record.]

Is it the end, or the evolution, of SIM

The $20 million granted Rhode Island through the State Innovation Model initiative by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is expected to run out in June of 2019.

However, according to sources, the SIM grant, like the state, will not fade away but evolve. Exactly what that means is unclear – as is what the source of the money will be in the state budget to sustain its future activities.

The future interrelated, coordinated efforts of the R.I. Office of the Health Insurance Commissioner, the SIM initiative, and the Care Transformation Collaborative-RI will hopefully be made transparent as part of the FY 2020 state budget process.

The future of UHIP

Looming over much of the ongoing state work on health care reform is the question: what will happen with the Unified Health Infrastructure Program, or UHIP, when the contract with Deloitte expires in March of 2019? Will a new contractor take over the project? Will the state file a lawsuit against Deloitte?

The other big question still pending is: what is the status of the reconciliation efforts with the feds regarding advanced payments made to skilled nursing facilities by the state to forestall insolvency caused by the failure to process Medicaid claims in a timely manner following the botched rollout of UHIP?

Health equity zones and neighborhood health stations

In all the discussions around care transformation and integration of screening for behavior health issues into primary care practices, the somewhat unexplored topic is how the ongoing work of nine health equity zones fits into the rubric of primary care transformation.

Further, with the opening of the new facility for the Neighborhood Health Station in Central Falls, which will have the capacity to serve more than 80 percent of the primary care and urgent care needs for most of the residents of Central Falls, how will that change the equation around care transformation on a community-wide basis?

Bridging the gap

Another important part of the conversation, not included in the agenda for the Care Transformation Collaborative-RI’s annual conference, was the work being done by Clinica Esperanza, in a program known as “Bridging The Gap,” an initiative to reduce health costs and improve metrics for uninsured Rhode Island residents.

Clinica Esperanza, a volunteer-run, free health clinic located in the Olneyville neighborhood of Providence serving uninsured patients, recently published data in The Rhode Island Medical Journal, demonstrating the positive clinical outcomes and potential fiscal impact of the chronic disease management program coordinated by the health care clinic.

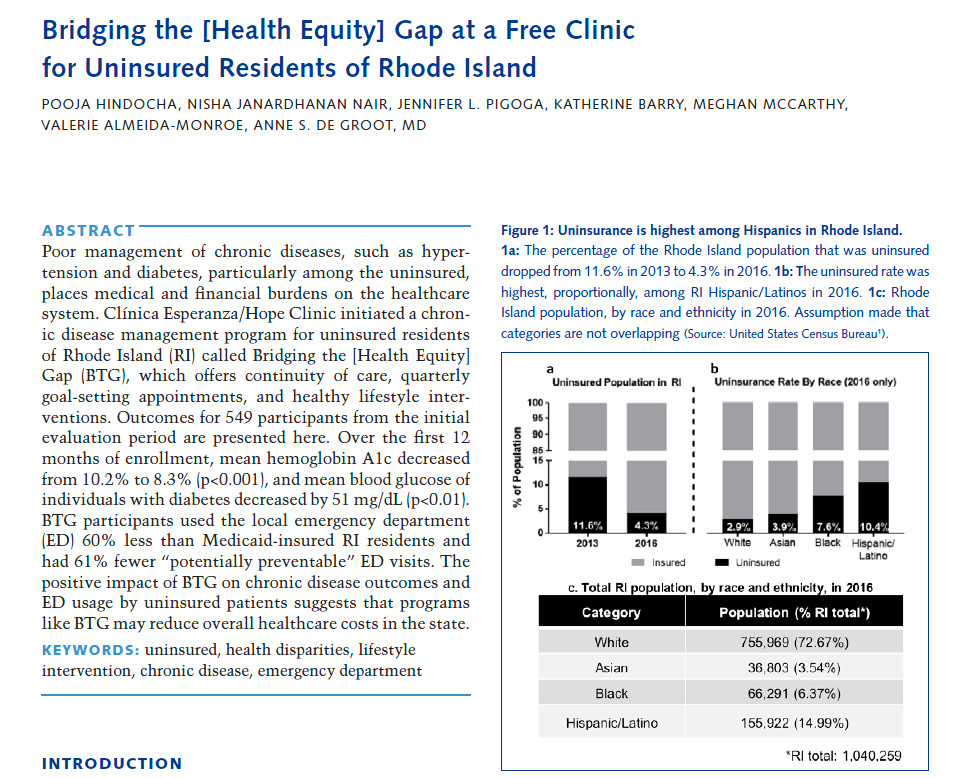

Hispanic Rhode Islanders are nearly four times more likely to be uninsured than the rest of the state’s population, according to the published study, titled “Bridging The [Health Equity] Gap.”

“The overall savings from the emergency department (ED) diversion aspect of BTG could be as high as $781,122 annually if the program were to be expanded to 8,000 uninsured Hispanics, statewide,” said Dr. Annie De Groot, the volunteer medical director of Clinica Esperanza.

“The health data measured by the study, Bridging the [Health Equity] Gap, makes perfectly clear that the health interventions that have the greatest impact are those that are community based, and that support health in the places where we live, learn, work, and play,” said Dr. Nicole Alexander-Scott, the director of the R.I. Department of Health, offering support for the Clinica Esperanza initiative. “Everyone deserves the opportunity to live a healthy life, no matter their ZIP code, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, level of education, level of income, or insurance status.”

Providence City Council President Pro Tempore Sabina Matos also offered her support for the initiative. “For the uninsured, a visit to the Emergency Department can be costly and can have serious effects on a family’s financial well-being,” Matos said. “The work that Dr. De Groot and Clinica Esperanza are doing for the Olneyville and Providence community is not only important but lifesaving.”