PROVIDENCE -- With one hand on the tiller and the other on the mainsheet, the sailor tests the wind, sensing the speed of the boat and the air slipping against his face. He shifts his weight and adjusts his course, and the sail billows around the landmarks in his field of vision. A moment of calm; then, swifter than a gull, he glides through an ever- changing perspective of his own invention.

A rising star in Boston’s world of corporate advertising, Mark Hartshorn began to weary of sacrificing his creative freedom to the demands of the client. Leaving his career as art director with hardly a glance behind, he returned to the Art Institute of Boston to get his M.F.A. in interdisciplinary forms and works on paper. An identity crisis flared again when the Community College of Rhode Island asked him to teach 4-D design and web-design. He was forced to come to grips with his ambivalence toward functional bias in the applied arts. He had to resurrect his detailed body of technical know-how for the sake of his students. Unexpectedly, he rediscovered his love for design.

As his sabbatical approached last September, Hartshorn was bursting to explore new possibilities of laser cutters, powerful cameras, and 3-D and 4-D imaging technology. But freed of teaching duties and facing an empty gallery, he began to feel overwhelmed.

One evening, after Chinese take-out, Hartshorn picked up the rice box, unfolded it and refolded it. He measured it, reached for paper and scissors and snipped out a tiny tabbed template that he creased and folded into a one-inch-high container. He made another. Before long, he was cutting and slitting colored paint chips and fitting and leaning them together like a house of cards. From there, he took off.

A visit to the studio

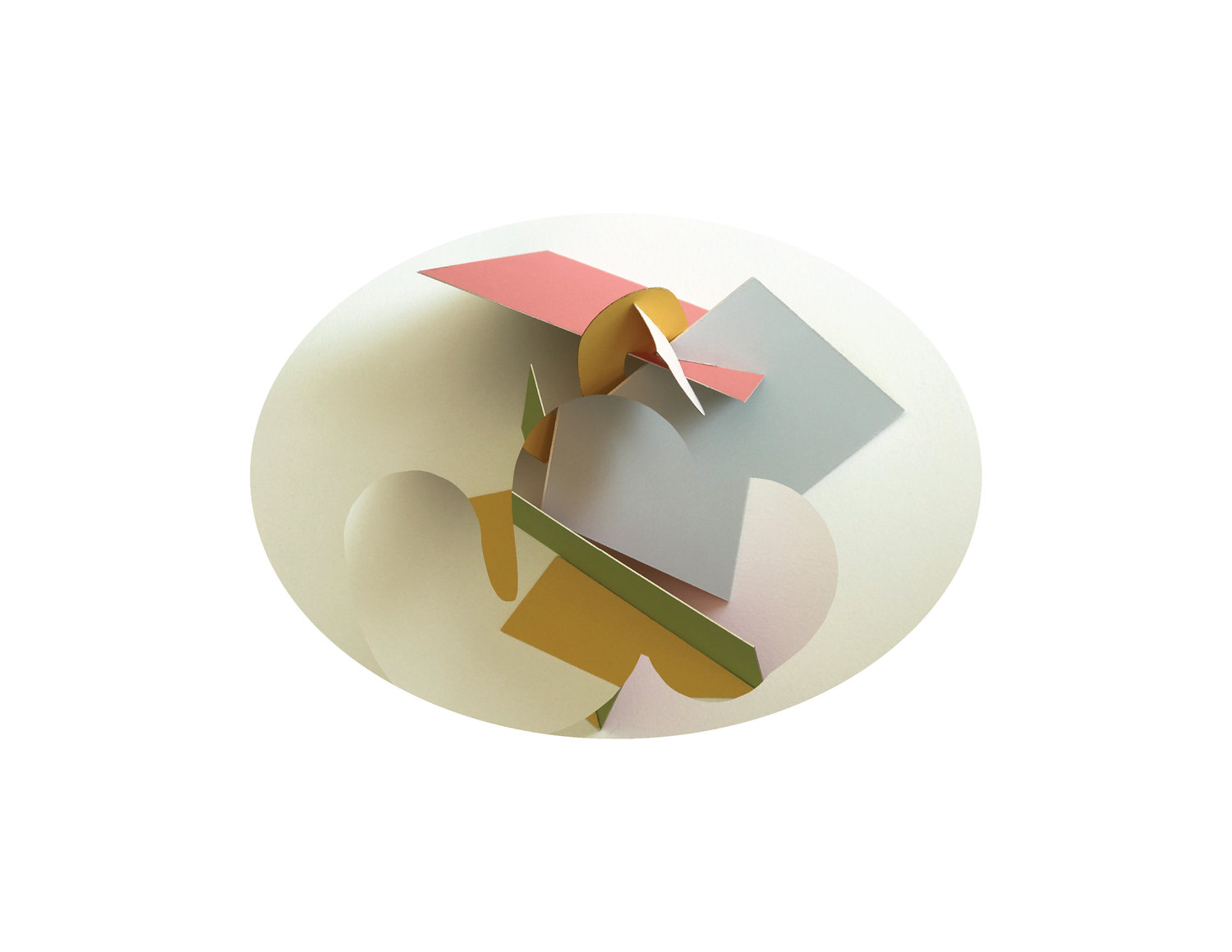

Months later, visiting Hartshorn in his studio, I watch him build a tiny sculpture on his desk from laminated colored rectangles. He leans a few lopsided ones together and balances a blue squiggle on top. The shaft of sunlight from the skylight challenges the beam of the desk-lamp, casting washed-out shadows. Hartshorn points to a pale green reflection bouncing off a red surface. He spins the lazy Susan. The muted planes approach and recede, brighten and fade. Edges melt and firm up again.

Hartshorn reassembles the modular parts in different ways. “It’s a dynamic collage, but it’s the same challenge as abstract painting. The geometric, stable forms you can rest in and understand. The quirky forms are more thought-provoking. You go back and forth between each one, and if you stand there long enough, you see other ideas and combinations.”

Going from two to four dimensions

He augments the complexity by taking bursts of photos of the moving target with his iPhone, followed by a few seconds of video. In these few steps, Hartshorn has traveled from two to four dimensions--- first, the colored planes, next, a diminutive sculpture spreading into space and finally, an object in motion over time.

“If I had a Plexiglass turntable, I’d be shooting it from underneath. It’s about being able to move around this. That’s what 3-D software enables at a “virtual” level.” But despite the allure of even more advanced technology, for now Hartshorn prefers the hand and simpler 2-D digital capabilities with which to modify his flat photographs.

“I like the speed of the camera. Just based on this, if you glued this and studied that, you could make endless works. Too many ideas! It’s the Achilles heel of my studio practice. One of the things I’m grappling with in my own work right now—I was using lasers, tools that make things that are produced quickly and look finished. They don’t yet have a staying power. Right now, I’m just refining a bunch of techniques. It’s a means to an end, a way to push forward into an idea or study.”

In Photoshop, Hartshorn preserves his delicate gradients of apple green, cinnamon, rust and ocher. He softens a few edges and masks others, whiting out shadows and sharpening contrasts. The screen images, born in a tangible, embodied experience, become subtle hybrids, at once familiar and otherworldly. The illusions of light and depth will change yet again in the transformation from LED colors to pigment on paper.

On the screen and in Hartshorn’s mind, the images are infinitely scalable, but to exhibit them as Giclée prints, he must commit to a fixed size. The framed digital images are almost ten times the size of the original sculptures. The abstract planar structures confront the viewer in surreal space, their odd twists and elisions hovering between silkscreen and photograph.

Hartshorn’s images preserve a Bauhaus simplicity within complex Cubist space. Lighting, both real and manipulated, is key. His experiments with technology introduce a more contemporary dialogue, combining the dynamic shifts of sculpture-in-motion of Lazlo Moholy-Nagy, the pulsating geometric edges of Frank Stella, and the biomorphic frenzy of Elizabeth Murray’s shaped canvases. Viewers may interpret as they wish---that’s the seductive nature of abstraction. But while the backstory may remain hidden, the vibrant forms tweak our imagination with their mystery and humor.

A walking professional toolkit, Hartshorn makes frequent digs at graphic-design convention. “I’m giving familiar things and messing with them. It’s a puzzle on purpose. The ‘happy face’ in the invitation image is ‘uncomfortable’; it doesn’t line up in the space. It almost looks like an accident. The hard and soft edge and focal points don’t work out; they’re not aligned the way a graphic designer would do. I like that.”

In the artist’s eyes, the 16 digital prints in the show are hardly “finished”—they’re only a point of departure. Change happens fast. The work before us now is a record of where the artist has been; it’s about process, not prediction. Come back a year or two from now, and there will be surprises. If there weren’t, it wouldn’t be art.

Elizabeth Michelman is a staff critic for Artscope Magazine and frequent contributor to Sculpture Magazine and DeliciousLine.org. A multidisciplinary artist, art critic, and independent curator with a studio in Waltham, MA, Michelman has shown painting, sculpture, video and installation art in New York, New England, and nationally for many years. Her 2-D works are currently on display in “Dot Conference” at Room83Spring Gallery in Watertown, MA and “That’s Cliché, or Not,” at Hallspace Gallery in Dorchester, MA.

http://www.elizabethmichelman.com

https://walthammillsopenstudios.com/portfolio/elizabeth-michelman

Author's Note: Knowing an artist and admiring their work is not enough to convince me to take on the grunt-work of writing about their art. I can't go forward unless I have come to understand and believe in the integrity of their process. Mark Hartshorn offers a fascinating case study in both the split and the overlap between the experimental spirit underlying a commitment to the process-orientation of art and the focused determination required for success in the design field.

We often find artists torn between an inner voice, fraught with anxiety, and the external forces that offer predictable reward, whether it be for a commercially viable art or a design solution responsive to market-driven demands that pleases the client. Hartshorn has lived both sides of the equation and not only knows, but at CCRI, teaches, the difference.

In following Hartshorn's work and teaching trajectory for the last ten years, I've seen him negotiate the dichotomy in values he speaks about in the interview. His art process pits his creative impulses directly against the demands of "good design principles" within a context that makes this struggle visually concrete. It's only his truthfulness toward his own (and his audience's) ambivalence toward these conflicting goals that can guarantee a successful resolution.

A similar essay titled "The Chips Have Fallen: Hartshorn’s Stretches Graphic Design at CCRI" was published in Artscope Magazine and Artscope Magazine OnLine, September 6, 2019. Reprinted (in modified form) by permission of Artscope Magazine and Elizabeth Michelman ©2019. All rights reserved.