A change of heart and mind

Chris Koller changes his mind about the opioid epidemic, arguing the need to adopt a public health prevention strategy for the diseases of despair

As the recent federal shutdown revealed, many American families are living paycheck to paycheck, surviving on a treadmill of debt, including many young families saddled with outrageous student loans. The recent emergency shutdown of natural gas supplies to Newport demonstrated how vulnerable whole communities have become, through no fault of their own.

Too many Americans have become members of the 21st century Joad family [characters from The Grapes of Wrath], watching as their small rural communities lose factories, farms, hospitals and the promise of a better economic future, often at the hands of equity investors and hedge fund managers.

The bottom line is about dignity and respect in work: providing jobs with good wages and an opportunity for advancement, with a safe, affordable place to live, and not the prospect, as Reel Big Fish once sang, “Well, I know you can’t work in fast food all of your life.”

Editors Note: Christopher Koller, the first R.I. Health Insurance Commissioner, has always been a pioneer when it comes to promoting efforts to reform health care, to reduce health care costs, and to make the costs of health insurance more affordable.

His efforts nearly a decade ago to create new affordability standards for commercial health insurance in Rhode Island put him in the crosshairs of many in the Rhode Island health care industry.

Under Koller’s leadership at OHIC, the first pilot program patient-centered medical homes under an all-payer framework, the forerunner of what became the Care Transformation Collaborative, was launched in October of 2008 with five primary care practices.

Today, the Collaborative includes 106 primary practices, including internal medicine, family medicine and pediatric practices, with some 750 providers participating across the network. Approximately 650,000 Rhode Islanders are receiving care from one of the practices – roughly two-thirds of the entire state’s population, even if the patients may not be aware that they belong to a patient-centered medical home.

Koller is currently the president of the Milbank Memorial Fund, which works to improve the health of populations by connecting leaders and decision makers with the best available evidence and experience.

In his most recent blog post, “The View from Here,” featured a remarkable change of heart for Koller, talking about the “diseases of despair” – alcohol, suicide and drugs, and the acknowledgement, as he wrote: “All the resources we can muster to address the epidemic of opioid deaths that has captured headlines and the attention of politicians will be ineffective unless paired with the economic and social equivalent of public health prevention.”

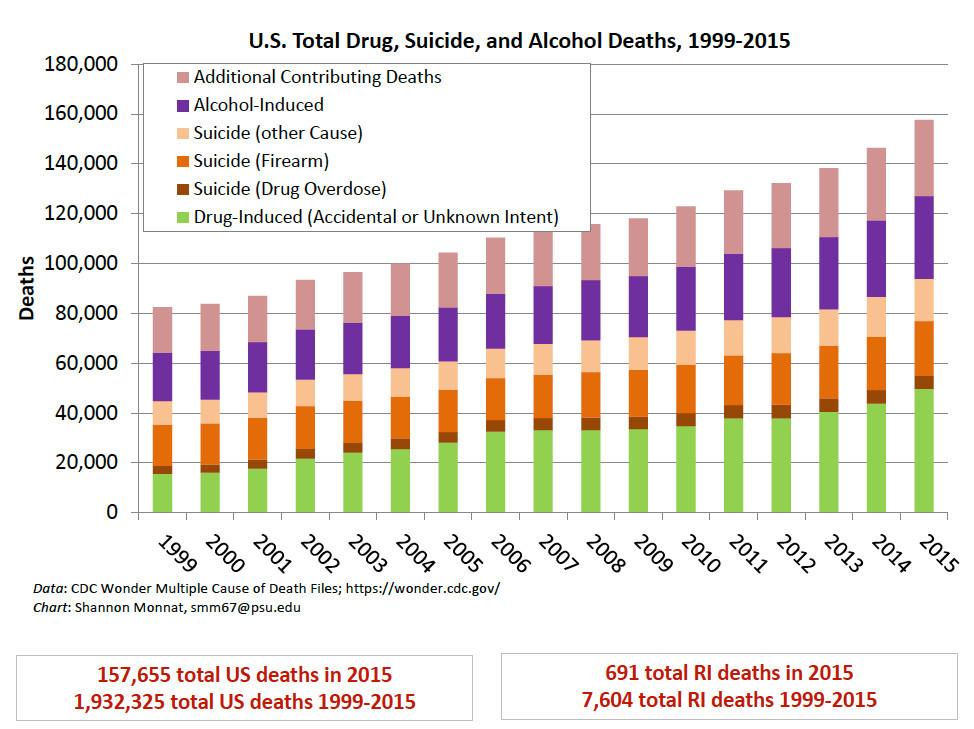

Two years ago, in February of 2017, ConvergenceRI first reported on the work by sociologist Shannon Monnat and her research into the deaths of despair, which identified the high mortality rates for Rhode Islanders between the ages of 25-34 as being among the highest such rates in the nation. [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “Study links deaths from drugs, suicide, alcohol to young adults.]

ConvergenceRI brought Monnat to Rhode Island College in 2017 to deliver a talk, “Landscapes of Despair: A Demographer’s Take on Drug, Alcohol and Suicide Mortality.”

Despite the best efforts by ConvergenceRI to report on the diseases of despair, and frequent questioning of government and community leaders, including many members of the Governor’s Task Force on Overdose Prevention and Intervention, the issue has always stayed well beneath the radar screen.

Perhaps, that may change now. Koller’s provocative post may prove to be an important sea change, allowing people to listen in new ways.

NEW YORK CITY, New York – I teach a public health course on the U.S. health system.

As the grizzled realist in the room, I remind my bright-eyed “public healthers” that being right is not the same as being effective. That while an ounce of prevention really is worth a pound of cure, it is not enough to hector the rest of us constantly.

And that to make prevention efforts work, they have to understand where all the money is in health care and how it got there.

Reversing course

I find myself doing the reverse, however, on a current health care topic. Are we really serious about reducing the “deaths of despair” that are rising in our country and appear to be driving a mortifying reduction in U.S. life expectancy for the second time in three years?

If yes – then all the resources we can muster to address the epidemic of opioid deaths that has captured headlines and the attention of politicians will be ineffective unless paired with the economic and social equivalent of public health prevention, of the kind promoted by a prominent U.S. social economist.

Last year, researchers at the Commonwealth Fund used their annual state scorecard to explore further the changes in the rates of death for suicide, drugs, and alcohol, first identified collectively as deaths of despair by Anne Case and Angus Deaton.

Their main findings were that:

• Death rates for all these factors increased by 50 percent between 2005 and 2016, driven primarily by a doubling in death rates for drug overdose.

• Death rates for suicides and alcohol, however, also increased by 25 percent.

• There was significant state-level variation in the aggregate rates of increase in death rates from these factors during this time period. In California, Texas, and Mississippi, combined death rates increased “only” 18 percent to 19 percent, while West Virginia, New Hampshire, and Ohio saw more than a doubling.

More resources

Efforts to treat the drug overdose epidemic have accelerated at the federal, state, and local level. The Feds have made significant additional financial resources available and state and local policymakers are learning effective strategies for reducing drug supply [with law enforcement efforts], preventing addiction [with mental health service access], and providing treatment [peer group counseling and medication-assisted treatment].

As is to be expected, the levels of comprehensiveness and effectiveness of these efforts vary significantly among jurisdictions, as demonstrated by different rates of increase – or, in some cases, even decline, in recent years.

Regardless of the attention given to the opioid epidemic, we should not let that distract health policymakers from the deeper message of Case’s and Deaton’s deaths of despair.

Imagine a 25 percent increase over 10 years in deaths per capita from breast cancer or obesity. A “war” on the condition would be declared. Congress would conduct hearings and allocate vast resources for research. Advocates would organize. Culprits would be sought and identified. Such was the case 30 years ago with AIDS.

Why no uproar?

Yet a similar increase in suicides and alcohol-related fatalities elicits no such uproar. Perhaps it is because opioids are a clearer foe and we can draw a bead on obvious perpetrators – the shameless peddlers of prescription painkillers.

More likely it is because despair cannot be attributed to a virus – a biochemical foe that can be identified, researched, and attacked. Instead the causes are social. Our researchers are not NIH clinicians but journalists, social scientists, and neighbors, like Sam Quinones [Dreamland], Arlie Russell Hochschild [Strangers in their Own Land], and J.D. Vance [Hillbilly Elegy]. Their conclusions are partial and messy. The pathogens can’t be definitively identified under a microscope: a lack of jobs, a failure of the political system, a failure of parenting to instill virtue.

Of course, for health providers, care must be administered to these victims, even if there is no equivalent to an antiretroviral therapy for despair. But prevention of these cases lies far outside the realm of health care – for all but the most expansive public health advocates.

Instead we must turn to the realm of the “dismal science” – economics. In her new book, The Forgotten Americans, veteran social economist and former Clinton administration official Isabel Sawhill focuses her attention on the population most susceptible to deaths of despair.

Defining her target as white, non-college graduates with an income below the U.S. median, and the problem as the loss of economic mobility for this population, Sawhill asks what can be done to help them become more engaged [and less despairing] members of their communities.

The lack of economic mobility

Recognizing that her challenge is cultural, not clinical, Sawhill proposes that any public policy to address the lack of economic mobility in this group promotes three core values – the dignity of work, the centrality of the family, and the importance of education.

Her specific policy recommendations are what she describes as “radically centrist” – a GI bill for career and technical education, universal national public service, refundable credits for low-wage workers paid for by higher estate taxes, tax policies that promote greater worker ownership and profit sharing, and changes in Social Security that promote the three core values and acknowledge the realities of longer lifespans.

Sawhill’s proposals attempt to address the conditions under which these “forgotten Americans” live – the social determinants of health that drive them into the country’s emergency rooms and pharmacies and drive up our health care spending.

She acknowledges that enactment of these proposals would require public sector agency – effective [if limited] actions by the very institutions of government in which people have diminishing confidence. Their enactment also expects individual agency – recognizing one’s duties as a citizen, parent, and worker.

Moving beyond endless triage

One can debate the merits and feasibility of these proposals. They certainly are socially challenging, and perhaps they may be politically unattainable or economically unsound.

But unless we are content to continue engaging in the endless triage of victims of despair – figuratively and literally administering naloxone over and over again – we must pay attention to the issues that Sawhill is addressing.

If anyone recognizes this truth it should be those of us who work in health care. We repeatedly treat [and pay for] these victims of despair. We know the need for prevention. We understand that both individual behaviors and social circumstances matter. We know that bad luck happens and mercy is necessary. And that doing repeatedly what does not work is Einstein’s definition of insanity.

A 50 percent increase in deaths from suicide, drugs, and alcohol constitutes a crisis. It is only the most graphic representation of a culture that is not providing hope and dignity to all its citizens. Better health care alone will not fix this – my “public healthers” are right. To be effective, as Sawhill proposes, we also have to work to change the economic and social rules.

Christopher F. Koller is president of the Milbank Memorial Fund. The story is reprinted with permission from the blog post published on Jan. 28, entitled: “Deaths of Despair: Prevention for a Growing Crisis.

Second editor's note: The alleged deceptive practices by the owners of Purdue Pharma, the Sackler family, to push its addictive prescription painkiller, OxyContin, revealed in discovery in the lawsuit brought by Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey, offer great insight into what is wrong with the pharmaceutical industry.

The lawsuit seeks to hold Purdue Pharma accountable for its deceptive practices. It also raises the questions: what do we need to do moving forward, as solutions. Does the way that the pain scale was added as a health vital sign need to be re-examined? When the Sacklers pushed a "blame the victim" media strategy, why did it find such a receptive audience?