Life cycle of health care in RI: busy being born, busy living, busy dying

As Memorial Hospital wrestles with staying alive financially, the conflict over the planned closing of its Birthing Center offers provocative questions and surprising answers about who speaks for the women and families of Central Falls and Pawtucket

Levy continued: “It will lead to a kind of class structure based on the ability to pay. Health care will start to look like the other sectors of our society.”

PAWTUCKET – In our lives, giving birth and watching loved ones die are perhaps the most emotional moments we carry with us as our own personal stories, rarely shared at a public microphone in a school auditorium.

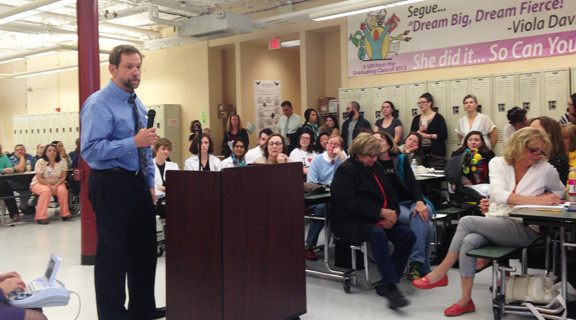

So it was cathartic to listen to those passionate and courageous enough to share their stories at a hearing held on March 14 by the R.I. Department of Health at Goff Junior High School on Newport Avenue regarding the Certificate of Need in reverse to close the Birthing Center at Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island, a Care New England hospital.

[Although the hearing was focused on the future of the Birthing Center, the organizers of the effort to keep the center open attempted to broaden the scope of the discussion to include the proposed closing of the Intensive Care Unit.]

As health department officials listened, including Dr. Nicole Alexander Scott and Michael Dexter, person after person, mostly women, stepped up to the mike and told their story, often amidst tears, about how the Birthing Center provided them such excellent care, contrasting that with what they often derogatorily alleged was the “industrial baby factory” at Women & Infants Hospital.

It made for a compelling story – and for great TV, no doubt – emotional pleas from women, babies on their hips, to save one of the community hospital’s key departments from closure.

The arguments were made – by a maternity nurse working at Memorial – that the hospital served the underserved populations of Central Falls and Pawtucket, those most likely at risk to fall victim to the social, racial and economic disparities of health care delivery. The likelihood that pregnant women would be able to travel by bus to either Women & Infants in Providence or Kent in Warwick was unrealistic, she claimed.

[Following the hearing, organizers of the effort to keep the Birthing Center from closing invited Pawtucket Mayor Donald Grebien to accompany them on a planned bus tour from Central Falls to the hospitals in Providence and Warwick; he tentatively agreed.]

A separate reality

The problem, however, was that despite the emotional outpouring, as sincere and heartfelt as it was, and as articulate as many were about the desire by women and families to have a “choice” in the way they delivered their babies that reflected their beliefs and concerns as patients, it was about a separate reality, one far removed from the actual numbers and the facts about where the mothers from Pawtucket and Central Falls chose to give birth.

And, it was disconnected from the reality that Memorial Hospital was bleeding out financially, a ruinous path begun under the previous leadership of former President and CEO Frank Dietz, who inexplicably had managed to spend down some $50 million during his last few years from an unrestricted hospital endowment fund, with little or no apparent board pushback or oversight.

What did it get spent on? Good question. [Dietz’s successor, Martin Tursky, quit less than a year after assuming the helm, to skedaddle back to Ohio, claiming urgent “family” responsibilities. It turned out he had arranged for a new job for himself back in Ohio. What were his reasons for departing so suddenly?]

No one testifying, however, mentioned the names of Dietz or Tursky at the two out of three hearings ConvergenceRI attended. [What would you want to happen – to have Frank dragged off a golf course in Florida and hauled back to Rhode Island? one health care advocate asked ConvergenceRI, responding to a question by ConvergenceRI wondering how the $50 million had been spent and whether it had involved alleged malfeisance.]

However laudable and compelling the effort to create an engaged community of women and families to keep the Birthing Center open, using the social media tools of Facebook to collect 324 double-side pages of signed petitions in favor of keeping the Birthing Center open and handing them to R.I. Department of Health officials at a March 17 hearing, their focus did not seem to be about how to keep Memorial itself open and operating, but rather how to preserve the Birthing Center as their personal right, a kind of birthright.

The missing facts

The basic disliked fact is that Memorial Hospital, for all its excellent care, was – and is – hemorrhaging money. As a business model, the acute care community hospital no longer works, reflective of the changing realities of health care delivery in the 21st century and the steep economic decline of the industrial manufacturing economy in Pawtucket and Central Falls.

There is also the painful reality, much like a hidden family history of misdeeds by a revered grandfather that no one dares speak up about at the dinner table, that Memorial Hospital’s fiscal woes can be blamed in part on the alleged fiscal mismanagement by Dietz, the president and CEO of Memorial Hospital for 47 years until his retirement in 2011. [Dietz stayed on as a member of the board and had a consulting contract after he left.]

How else can you explain the loss of some $50 million in unaccounted spending from an unrestricted endowment at the hospital during the last few years of Dietz’s administration, in advance of Care New England’s acquisition in 2013?

One case in point, directly applicable to the Birthing Center: Memorial Hospital hired, under Dietz, a chief of obstetrics, at a salary of about $350,000, who allegedly could not be involved with direct patient care because he did not have and could not obtain malpractice insurance, four different sources told ConvergenceRI. He allegedly served in that position for three years, at a cost of more than $1 million, if you factor in benefits.

When Care New England took over Memorial in 2013, it was already bleeding profusely financially. In the last three years, despite investing millions, Care New England has been unable to staunch the flow of red ink.

By the numbers

Today, the 298-bed acute care community hospital has a daily census of around 50 beds being used by patients, according to hospital officials.

The number of births at Memorial in 2015 was 427, according to the R.I. Department of Health, which breaks down to an average of about 1.17 births a day. The average patient census is three patients a day, and the majority of the time – 59 percent – there are three or fewer patients, according to hospital officials.

To put that into perspective, the birth rate in Rhode Island has been relatively stable for the last four years, averaging about 10,500 births a year.

The highest number of births in 2015 occurred at Women & Infants Hospital, which delivered 8,858 babies – an average of about 25 births a day, the largest number in the state, according to R.I. Department of Health Statistics.

The lowest number of births at hospital was at Landmark Medical Center in Woonsocket, which reported 208 births in 2014, or an average of .6 births per day. Indeed, Landmark is hovering at the 200-birth level, considered the bright line by which state certification could come into play, deeming that at a such low-volume facility, the risk and safety factors could become untenable. [As part of the 2013 agreement in the purchase of Westerly Hospital by Lawrence + Memorial Hospital in New London, Conn., the obstetrics unit at Westerly was closed down.]

Who’s being served by Memorial’s Birthing Center?

So, how many women from Pawtucket and Central Falls actually use Memorial Hospital’s Birthing Center? That’s a key question that gets to the heart of the viability of the facility and proponents’ arguments around keeping the Birthing Center open because it was serving underserved communities most at risk.

In 2014, there were 322 births by women from Central Falls, and 978 births by women living in Pawtucket, for a total of 1,300 births in the two primary urban communities served by Memorial Hospital, according to the Rhode Island KIDS COUNT 2015 Factbook.

By the numbers, those 1,300 births in 2014 were about seven times the number of children born at Memorial Hospital from mothers living in Central Falls and Pawtucket, a total of 188 births, according to Kidsnet, the database managed at the R.I. Department of Health.

In comparison, in 2014, there were 251 births from other areas of Rhode Island at Memorial’s Birthing Center, and another 53 from out of state.

Translated, 304 of the births at Memorial in 2014 were from outside of Pawtucket and Central Falls, while 188 births were from those cities: some 60 percent of all births at Memorial were from outside Pawtucket and Central Falls.

In 2015, that same trend continued: some 58 percent of all births were by mothers living outside of Pawtucket and Central Falls.

The total number of births at Memorial declined to 427 in 2015 from 492 in 2014, a decline of 13 percent, according to the Kidsnet data.

The number of births from Central Falls and Pawtucket delivered at Memorial’s Birthing Center also declined to 157 in 2015 from 188 in 2014, a decline of 16 percent.

The numbers speak very loudly here: most mothers in Central Falls and Pawtucket do not deliver their babies at Memorial Hospital, by a seven-to-one margin. Further, 58-60 percent of the births occurring at Memorial Hospital are from mothers living in other areas of Rhode Island or from out of state. Why is that?

Crunching the numbers

Most of the expectant mothers under the managed Medicaid program that receive health care from Blackstone Valley Community Health Care, the community health center that provides care for most of the managed Medicaid patients in Central Falls and Pawtucket, deliver their babies at Women & Infants Hospital. In 2015, that was roughly 250 births, compared to the 157 delivered at Memorial’s Birth Center from those two cities.

Digging deeper, in Central Falls, in 2014, the total numbers of infants born at highest risk were revealing. Out of a total of 322 births, 111 mothers did not have a high school diploma, 245 were single mothers, and 44 mothers were younger than age 20, according to Rhode Island KIDS COUNT Factbook.

Similarly, in Pawtucket, in 2014, out of a total of 978 births, 152 were to mothers without a high school diploma, 577 were to single mothers, and 67 were to mothers younger than the age of 20.

Translated, it appears that Women & Infants is the hospital that is caring for the mothers most at risk, by the numbers, in Pawtucket and Central Falls. In turn, Memorial Hospital is operating much more like a boutique birthing center, serving not the high-risk mothers in the communities of Pawtucket and Central Falls, but rather those mothers from outside of the service area that desire a different kind of birthing experience. [Of course, there is no wall around a hospital determining who can be served there.]

Which is not to say that the Birthing Center does not provide excellent care, and provide a different, desired kind of valued approach to birth that seeks to better serve the needs of the mother and child – a valuable service.

As many of those who testified at the third hearing on March 17 in Central Falls at the Segue Institute for Learning on Cowden Street, it was a matter of the mother’s choice of what they perceived as the best possible care when giving birth – as testified to by many residents of Barrington, Providence, North Providence and even out-of-state mothers.

But the facts tell a much different story than the emotional testimony at the hearings: the women served by the Birthing Center at Memorial Hospital are not, by in large, from the poor, underserved communities of Pawtucket and Central Falls.

That said, moving forward, the disliked question was this: could the valued attributes of the Birthing Center find a new home at Women & Infants?

From the hospital system’s perspective, the chief of nursing, Angelleen Peters-Lewis, RN, Ph.D., SVP, testified on March 17 in Central Falls that there was a willingness to accommodate.

Yet, for most of the advocates of keeping the facility open, their answer was an adamant no, reflective of their apparent unwillingness to compromise, a virus that seems to afflict much of our political decision-making these days. “It’s about the culture,” one nurse midwife said, and that culture, she argued, could not be replicated outside of the Birthing Center in Pawtucket.

A tale of two sides

At the hearing in Central Falls, the proponents of keeping the Birthing Center open at Memorial Hospital loudly cheered and applauded all the testimony of those who supported their position.

However, they were silent after Dr. Jeffrey Borkan, chair of the Department of Family Medicine at the Warren Alpert Medical School at Brown University, who oversees the residency program at Memorial Hospital, finished speaking.

Borkan said that he was following the same advice that he gives to residents: always say what’s on your mind.

For Borkan, who has spent much of his career at Memorial Hospital, the reality was that the community hospital in an urban setting no longer worked financially. “I think it’s over,” he admitted.

In the same way that factories have closed down and the jobs have left, the same was true for community hospitals such as Memorial – despite the efforts to keep in running with sticks and glue, despite the efforts by Care New England – because the nature of the health care industry had changed.

“The hospital industry has changed,” he said. “We have tried to keep Memorial open. It was special; it is special.”

Borkan did not blame Care New England, which he said had poured in “millions and millions to try to keep the hospital afloat.”

Now, it was time to mourn the losses and move on, and create a new future, Borkin continued.

“We need to look forward and ask: where do we go from here? We need to mourn for what is lost and move on.”

When Borkan finished, there was an awkward silence in the makeshift hearing room. For many in the audience, it had been a difficult opinion to hear, and it was very much a disliked message.

On the other side of the coin was the testimony offered by Christopher Callaci, the legal counsel for the United Nurses and Allied Professionals, or UNAP, representing the nurses at Memorial. Speaking without using the microphone, Callaci challenged the legality of the hearing process, arguing that it should be immediately suspended, because not enough notice had been given.

Callaci also challenged the legal authority of Care New England to act under the decision made in 2013 by state authorities under the Hospital Conversions Act, quoting from the decision.

However, the actual wording of the decision may not support Callaci’s contention, because it said no elimination of services provided was “envisioned” in the three years following the acquisition.

The language in the written decision, according to sources familiar with how the document was produced, specifically did not forbid Care New England from terminating services, given the dire financial straits facing the hospital.

The contingent supporting keeping the Birthing Center open erupted with cheers when Callaci finished.

What happens now?

The testimony at these hearings was not occurring in a vacuum. Lifespan, the largest hospital system in Rhode Island, has a pending request before state health authorities to build and open a new obstetrics facility to handle up to 2,500 births a year – about one quarter of the state’s annual births – in direct competition with Women & Infants Hospital, to be located only a few hundred yards away.

The projected cost of Lifespan’s new facility was $35 million to build and another $15 million to run.

CharterCARE also had submitted a request to open a new obstetrics unit on its Providence campus.

The decision to propose building new obstetric facilities in state such as Rhode Island, with a relatively stable birth rate averaging around 10,500 for the last five years, does not appear to have much to do with serving an unmet need. Rather, it appears to be driven more by fierce competition to capture a larger share of the women’s health market, in a struggle between Lifespan and Care New England.

At the same time, Care New England is in the midst of closing a new partnership agreement with Southcoast Hospital system headquartered in New Bedford, Mass.

Further, there is an effort by Neighbors Health System, a Texas-based firm, to launch a series of freestanding emergency care facilities, with the first one in West Warwick and second one proposed in Bristol. That request is now before the Health Services Council.

And, there is also a planned Medical Tourism facility proposed for Warwick at the Crowne Plaza Hotel by the Carpionato Properties.

Despite a number of studies conducted in the last few years, there does not appear to be a coherent statewide health care plan upon which to make fact-based decisions moving forward. The responsibility will fall to Dr. Nicole Alexander Scott, director of the R.I. Department of Health, who reports to Elizabeth Roberts, secretary of the Executive Office of Health and Human Services, who, in turn, reports to Gov. Gina Raimondo.

Whose ox gets gored?

Despite the fact that the health care industry sector is the largest private employer in Rhode Island and generates north of $16 billion in revenue annually, that sector has been surprisingly absent from the discussions the state’s future economic development.

While there have been two working groups commissioned by Raimondo – one to reinvent Medicaid, the other to control medical costs – their focus has been on reducing state budget expenditures and state medical costs, not on what is needed to support and strengthen the sector.

The changes, proposals and requests now before state health care authorities come at a time when the entire business model for health care delivery is changing dramatically – a topic that ConvergenceRI has reported on extensively in the last three years.

The disliked fact is that Rhode Island is in the process of being consolidated and colonized by out-of-state health systems, by both not-for-profit and for-profit entities.

It may prove instructive then, to pay attention to what Raimondo told reporters recently, as reported by WPRI’s Ted Nesi on March 17.

According to Nesi: Raimondo told reporters earlier this week she has sympathy for the “very tough situation” faced by women who’d planned to deliver their babies at Memorial.

“As a mother my heart goes out to these young women who are planning to have their babies and then – oh, oops, you might not be able to at this birthing center,” she said.

But the governor also seemed to indicate her administration is unlikely to block Care New England’s move. “They have a business model, and they need to figure out if they can sustain what’s going at Memorial,” she said.

“These kinds of difficult decisions are going to be made as we face a new reality of the health care system,” Raimondo said. She added that it’s “no secret” [that] a 2013 state study found the state has roughly 200 more hospital beds than it needs, saying: “It’s just a fact – we’re going to need fewer hospital beds because more and more procedures are being done out of a hospital bed.”

[Oh, oops, Governor: remember your promise back in January, sealed with a handshake, to sit down with ConvergenceRI for a one-on-one interview? Can you please ask your communications person, Marie Aberger, to call to schedule an interview in response to my pending request?]

Health, health care, health equity, and access to care

It’s often confusing to talk about the differences in the metrics around health care delivery and population health in accountable entities that are reimbursed through bundled payments for a continuum of care, and the benchmarks for achieving health equity in communities and neighborhoods outside of the health care delivery system.

It depends on what you are counting: population health for the groups of individuals who self-select to be served by a medical practice or a hospital, and the health and well being of those who live in a particular neighborhood and zip code.

The advocates who have forcefully opposed the planned closing of the Birthing Center did so at hearings by claiming they are speaking on behalf of the underserved populations of Central Falls and Pawtucket. But, by the numbers, they were not: in 2014, most women giving birth who lived in Central Falls and Pawtucket did not deliver their babies at the Birthing Center, by about a seven-to-one ratio. Further, most of the births occurring at the Birthing Center – 60 percent in 2014, 58 percent in 2015 – were for women who lived outside the cities of Central Falls and Pawtucket.

That said, the quality of care for women and their families afforded by the Birthing Center at Memorial Hospital clearly resonated with many, particularly for those who wanted more “choice” in their medical care.

As one woman testified, we have choices for the kinds of coffee we can drink; why not in health care? It’s a matter of how much that health care will cost, and who will pay for the losses if it is not profitable? And, can the value of an alternative birthing center in Rhode Island be preserved in another institution?