How to solve wicked problems

Rochester Roots, an educational program in Rochester, N.Y., teaches elementary school students entrepreneurial skills of competence, connectedness and autonomy they need to survive and thrive. Can it offer Rhode Island a collaborative model of diverse community engagement?

Innovation is an iterative process; it rewards nimbleness and flexibility. Investing in communities and neighborhoods, and the elementary school students that live there, create a different kind of return on investment for Rhode Island to consider.

ROCHESTER, N.Y. – Roots has many meanings, connotations and connections to our world today. The band known as Roots is the house band for Jimmy Fallon, first with Late Night and currently with The Tonight Show, as a Google search will quickly reveal.

There is the broader definition of roots music, the convergence of blues, jazz, country and western, folk and other indigenous forms of American musical expression. [The 19th annual Rhythm & Roots Festival will be held in Charlestown Sept. 2-4 this year, for instance.]

Roots is also the name of the popular TV miniseries aired in 1977, an adaptation of Alex Haley’s book, Roots: The Saga of an American Family, telling the story of the slave Kunta Kinte, and his descendants, drawing a 100-million TV audience when it was first broadcast.

A remake of the TV miniseries, also named Roots, will debut next week, airing over four nights beginning on Memorial Day on the History, Lifetime and A&E channels. The producer for the series is LeVar Burton, who originally starred as Kunta Kinte in the 1977 production.

Roots promises to be trending – and to rekindle the discussion about America’s historic relationship to the economic realities of slavery, both nationally and here in Rhode Island, at a time when racial divisions and disparities are at the forefront of our politic and cultural conflicts.

New roots

That discussion, like much of the conversations around health, social and economic disparities, has a broad convergence to the growing economic gap between the very rich and the rest of our society, and with it, the disappearance of the American middle class, which is slipping away faster than the ice shelves in Antarctica.

Here in Rhode Island, there are any number of community-based strategies and solutions attempting to take on this conundrum: neighborhood health stations in Central Falls and in Scituate; health equity zones in 11 communities; the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s Working Cities Challenge in Rhode Island, targeting the inequality of economic opportunity in 13 communities; and most recently, the new Invest Health initiative award for Providence, funded in part by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

From the Rhode Island Foundation’s policy leadership in its philanthropic efforts to the Brookings Institute’s strategic analysis of the state’s future economic potential, the goal has been to unlock and to coax and to advocate for public-private partnerships to achieve a more sustainable approach to investment in community to spur growth. [Of course, that depends in large part on how you define community, investment, neighborhoods and equity.]

It has become one of the insistent, rhetorical and sampled drumbeats in Gov. Gina Raimondo’s campaign to “make it in Rhode Island,” touting her economic development efforts: “In order to keep making progress, we have to provide opportunity for all Rhode Islanders,” as she said in a recent news release.

In Raimondo’s view of the world, that translates to being able to: “strengthen neighborhood schools, help Rhode Islanders build the skills that matter, so that they can compete for the jobs of the 21st century economy, prepare high school students for college and career, make college more affordable for more families, and support recent college graduates with student loan forgiveness and first-time home buyer support.”

All laudable goals; all translated into bite-size, fast food phrases that play well within the framework of an electoral campaign. The larger question is this: how do all these efforts connect, link up and interact as part of Rhode Island’s innovation ecosystem? Good question.

[As the song, “Compared to What,” once asked, in its jarring juxtaposition of the social myth of equality and the economic reality of poverty in a stratified American society: “Possession is the motivation that is hanging up the goddamn nation/looks like we always end up in a rut, trying to make it real – compared to what?” See the link below to YouTube of Les McCann and Eddie Harris’s version.]

The reality is that Rhode Island, because of its size, often serves as a working laboratory for cultural and economic change, sometimes ahead of the wave, sometimes behind, but almost always as an island, often in a kind of self-imposed isolation. [As if the world ended at the borders of the 401 Area Code].

There is, however, much that could be learned by Rhode Island in its efforts to develop new community roots from the experience of Rochester Roots, and the way it has successfully grappled with the challenge, as it has termed it in the vernacular, “How to solve wicked problems.”

Rochester Roots

It is easy to find many similarities between Rhode Island and its urban core and Rochester, as described by Jan McDonald, executive director of Rochester Roots, known as ROOTS, in her recent essay about the work of the not-for-profit agency serving at-risk populations in that city, and its focus on teaching elementary schoolchildren entrepreneurial ways of thinking to build competence, connectedness and autonomy.

“We are the fifth poorest city among the top 75 U.S. metropolitan areas, third for neighborhoods in extreme poverty, and the poorest urban school district in New York State,” McDonald wrote.

“ROOTS is headquartered in a city with a history built on sociological, ecological and technological systems innovations,” she continued. “We draw from a rich agricultural environment, a cluster of over 21 colleges and universities, including Cornell University, and, most recently, Rochester Institute of Technology’s Golisano School of Sustainability.”

Rochester had a strong historical link to its 20th-century, technology-based economy: the city was known historically, McDonald wrote, for its companies such as Kodak, the “World’s Image Center,” founded by entrepreneur George Eastman.

It was also once known as “The Flour City” for its once thriving flour mills located along the Genesee River; and now, as “The Flower City,” for its historic lilacs located in Highland Park that was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted.

Rochester also served as the former corporate headquarters of Xerox, known for its leadership in photocopiers, and Bausch & Lomb, known for its leadership in optics.

Further, Rochester’s innovation ecosystem benefited from a strong cultural legacy for independent political thinking, the home to Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass.

“Throughout our history, prosperity and scarcity have gone hand-in-hand,” McDonald wrote. “Decades of economic decline have now left our city with challenges to improve the state of education, health, jobs and community development, especially for our underserved citizens.” Sound familiar?

Changing demographics

As McDonald documented, in 1950, the city’s population was 332,488. The U.S. Census Bureau reported that, at that time, Rochester’s population was 97.6 percent White and 2.3 percent African American/Black.

Since then, the city has lost one-third of its population due to job losses from major downtown employers, including Kodak, which filed for bankruptcy in 2012.

McDonald continued: “White flight has left neighborhoods racially isolated. While mostly white, affluent suburbs surround our city, poverty, even in suburban communities, is growing. The 2010 Census reported that Rochester as a whole has a population of 43.7 percent White, 41.7 percent African American/Black, and 16 percent Hispanic, resulting in a significant shift in demographics.”

Overall, she wrote, 34 percent of our citizens and 53 percent of Rochester’s youth live in poverty. “Our neighborhoods and schools are the feedback loops exposing our dilemma.”

At a crossroads

The current mayor of Rochester, Lovely Ann Warren, elected in 2014, described the city as a “tale of two cities,” according to McDonald.

One city is vibrant, hopeful, wealthy, and highly livable; the other suffers from escalating poverty, dysfunction, unemployment that is higher today than it was during the Great Depression – and a deficient educational system, according to Warren’s description. Sound familiar?

The Rochester City School District has the highest poverty rate among the “Big Five” districts in the state, according to McDonald. To make matters worse, in 2014, its high school graduation rate was recorded at 51 percent, with only 9 percent of its Black male student population graduating.

Some 86 percent of the city’s students overall qualify for free or reduced price lunch – an indicator of an unsustainable system. In 2013, the school district took advantage of the community eligibility option to provide free lunches for all students.

“Our city has become experts at the institutionalized feeding of our poor from local, state and federal emergency feeding programs,” McDonald wrote. “Despite the efforts of our multi-million-dollar food bank system, we have failed to uplift our poorest citizens and create a pathway out of poverty. We have failed to address the educational, entrepreneurial and health needs of Rochester’s poorest citizens. We have failed to provide a means of self-reliance for the most vulnerable of our citizens: our youth.”

A solution

Building upon the results of research and pilot programs to implement a new, healthy urban food system model, one that linked food education, food processing, food distribution and food production, ROOTS has launched a curriculum to engage elementary school students in grades PreK-6 to learn the fundamental principles of living systems sustainability: resilience and adaptation.

The ROOTS solution: “To expand our pilot program to develop the next generation of citizens who are participants in the food system through their involvement in decision-making, entrepreneurial product development, food distribution, and scientific discovery,” McDonald wrote.

The curriculum development was based upon an influence modeling process that involved hundreds of community stakeholders, students and teachers, creating buy-in. This process, facilitated by Sustainable Intelligence, LLC, has now been adopted by the ROOTS students to stimulate critical thinking, within a whole systems approach.

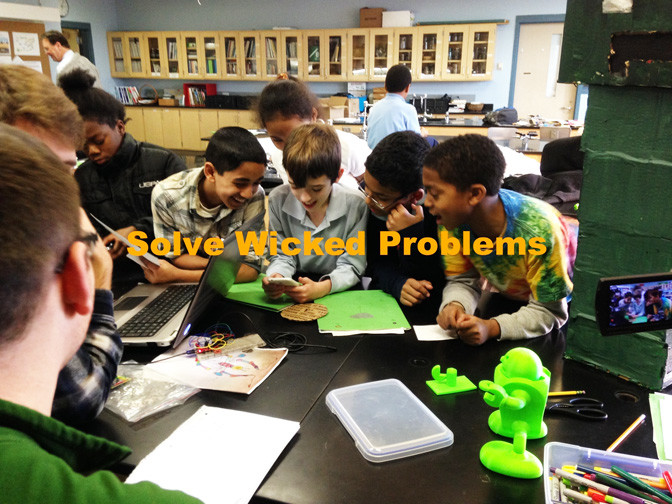

The elementary school students are now working alongside university students, farmers and experts, McDonald explained, in order to “solve the wicked problems of sustainability for the 21st century, while improving food security in the future.”

In doing so, the initiative seeks to rebuild “the entrepreneur spirit that our city was once known for, and to build agency for the community's own sustainable well-being and well-becoming, while rebuilding the community’s direction connection to the source of their livelihood and to nutritious food.” Sound applicable to Rhode Island?

The working hypothesis is that the development of some 26 “urban sustainability laboratories” and entrepreneur education workshops will result in evidence-based improvements in 11 specific outcomes identified in the research conducted under the earlier urban agriculture and community gardens study.

According to McDonald, part of the initial pilot, an in-school and after-school program known as “Bringing Science to Life,” was a huge success in merging academic skills with student-initiated entrepreneur projects. It attracted the participation of engineers, who helped develop tools and equipment for the student business prototypes, such as sensor networks, adaptive high tunnels, horticulture labs, robo-composters and lip balm assembly lines.

These partners include: engineering students from the Rochester Institute of Technology; modeling and stimulation expertise from graduate students at Arizona State University; consultants from Sustainable Intelligence, a local firm focused on community and business sustainability; and Mason Farms, a 750-acre certified organic farm using Integrated Pest Management methods.

This learning ecosystem, McDonald continued, provides participants with a rich multicultural and intergenerational social relationship-building experience – across academic institutions, businesses and communities.

To SEE is to believe

Under the ROOTS’ collaborative approach to what it calls “Sustainability Education & Entrepreneurship, or SEE, the program creates connectedness through a team approach to provide what is described as: a “deep-learning experience for developing awareness, expertise and critical thinking for sustainability,” with the capability to transcend the “wicked problems” being faced.

The model of learning combines academic theory, an integrated curriculum, and a hands-on practice, brought together through critical thinking and decision-making within a “sustainability framework.”

From a technical educational standpoint, it uses what is known as model-based inquiry, system dynamics modeling, and graph theory analytics. Translated, the students develop critical thinking skills that can be measured as results that are more predictive to success than, say, standardized testing.

The plan is to test the hypothesis in order to scale up the ROOTS program nationwide, working with Digitalmill to develop educational games that replicate the work, develop a STEAM [Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Mathematics] platform, and to encourage students to develop critical thinking skills within a sustainability milieu.

[The game initiative was funded through the Farash Foundation, building upon a USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture Community Food Projects competitive grant award to ROOTS in 2015.]

The fruits of labor

One of the programs in the first year was to develop youth entrepreneurs in the “Stand On My Own Two Feet Squared” school day program. Elementary school students in the third through sixth grades participated in the research, design and building of 75 new raised-bed learning gardens built on the school grounds.

As part of the process the students “self-determine” what will be planted in a two-foot by two-foot garden within a four-foot by four-foot raised bed.

They were provided with a $5 seed budget and challenged to generate income from the sale of their crop, value-added product, or service – and to create a Ph.D.-style poster of their research.

The work of the students will be featured at a SEE event on June 11 at the Rochester Museum and Science Center.

Some of the examples of the more than 90 student entrepreneur project prototypes in development include:

• Fruit Sorbet Infusions – Healthy desserts made from fresh fruit and fruit juices

• Bunches of Blueberries – If you’re feeling berry blue, my berries promise to cheer you

• Livi’s Tomatoes – Naturally grown without chemicals or artificial plant fertilizers

• Be-Rock Burdock – Be in love with my burdock and be in love with your health

• Zooming Zucchini Jam – Sweet & sassy

• Flying Saucers Herbal Tea – Tea that is out of this world

In addition, under Game Design, the student projects include:

• Real Life Timeline Game – Life-course decision-making

• Mastering Coding Language – Decision-making tool

• Power Growing Game – Learn about growing dynamics and seed saving

• Farm Market Game – Teaches life cycle of a farm from seed to market

Further, student prototypes for entrepreneur businesses include:

• f [Flowers = Happiness] – Heirloom flower plants and flower earrings

• The Balm – Lip balm product using medicinal plants

• Worm Composting Bin – Recycles plant and paper waste into compost

• Papermaking – Seed embedded bowls and cards

• Adaptable Palletized Raised Beds – Designed for ease of movement

• Invention Creation Center – Helping others with their entrepreneur businesses

Finally, under Multidisciplinary Senior Design Team Engineered Systems, the student projects include:

• Robo-Composter – Grinds paper, plant and food waste and activates composting process

• Stackable Seed Starter Laboratory – Controlled test lab

Measuring outcomes

From an educational perspective, the methodology follows a framework to encourage critical thinking: perception, interrelatedness, articulation, boundary, knowledge generation, research, resources, wellbeing, reflection and action.

In terms of outcomes and results, the hypotheses being tested and measured as part of this effort include:

• Do students who have assimilated use of this process improve critical thinking skills? How do we measure critical thinking?

• Does this process increase students interest in STEAM over the long term? Can we follow them from 6th grade to graduation?

• What tools are replicable and can become part of a game simulation?

• Is academic achievement improved by focusing on critical thinking?

• Does the Sustainability Education & Entrepreneurship [SEE] program act as a powerful tool for competence, connectedness and autonomy?

Beyond foodies

Here in Rhode Island, there has been a concerted effort to create a food industry cluster that can be connected to economic development, to take advantage of efforts to rebrand the state as a “culinary valley.” [See link to ConvergenceRI story below.]

The recent appointment of Sue AnderBois on May 10 to serve in the newly created position as director of food strategy for Rhode Island moves that effort forward.

The position, funded for two years from foundation grants from the Henry P. Kendall Foundation, the John Merck Fund and Main Street Resources, seeks to create policy for the entire food system in Rhode Island, from farms to supermarkets to restaurants – and beyond.

Economic policy research conducted in 2013 by The Fourth Economy, a firm based in Pittsburgh, which found there was a nascent food cluster in Rhode Island. From the renown of its restaurants to its training of world-class chefs at Johnson & Wales University, from its efforts to promote farm-to-table agriculture through FarmFreshRI to its innovative public health initiative, Food on the Move, to provide fresh fruits and vegetables to underserved communities, Rhode Island does have much to work with.

There are also the efforts underway as part of the Sankofa Community Initiative to build an urban farm connected affordable housing in the West End of Providence, with a permanent space for a community market.

What is missing from the equation is the educational curriculum component that Rochester Roots is bringing to market.

Perhaps AnderBois should consider a trip to Rochester to learn more about what is happening with the SEE program, and to explore how the program might be exported to the public schools in Rhode Island.

For more information, go to www.rochesterroots.org